Abandoning the Hindrances

Whoever has gained release from the world, is gaining release, or will gain release, all of them have done so by abandoning the five hindrances, the mental impurities that weaken wisdom, and by firmly establishing their minds in the four abidings of mindfulness, and by developing the seven factors of enlightenment as they really are. This is how they have gained release from the world, are gaining release, or will gain release.

AN10.95

Abandoning the Five Hindrances: Overview

The practice of Abandoning the Five Hindrances is the purification of the mind from the mental impurities that obstruct the arising of wisdom. These hindrances are rooted in habitual tendencies and defilements that prevent us from sustaining Right Mindfulness, dwelling in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, and maintaining a concentrated and collected mind.

They obstruct our ability to discern more subtle states of mind, hinder our entry and abiding in jhāna, and ultimately block our progress on the path to liberation.

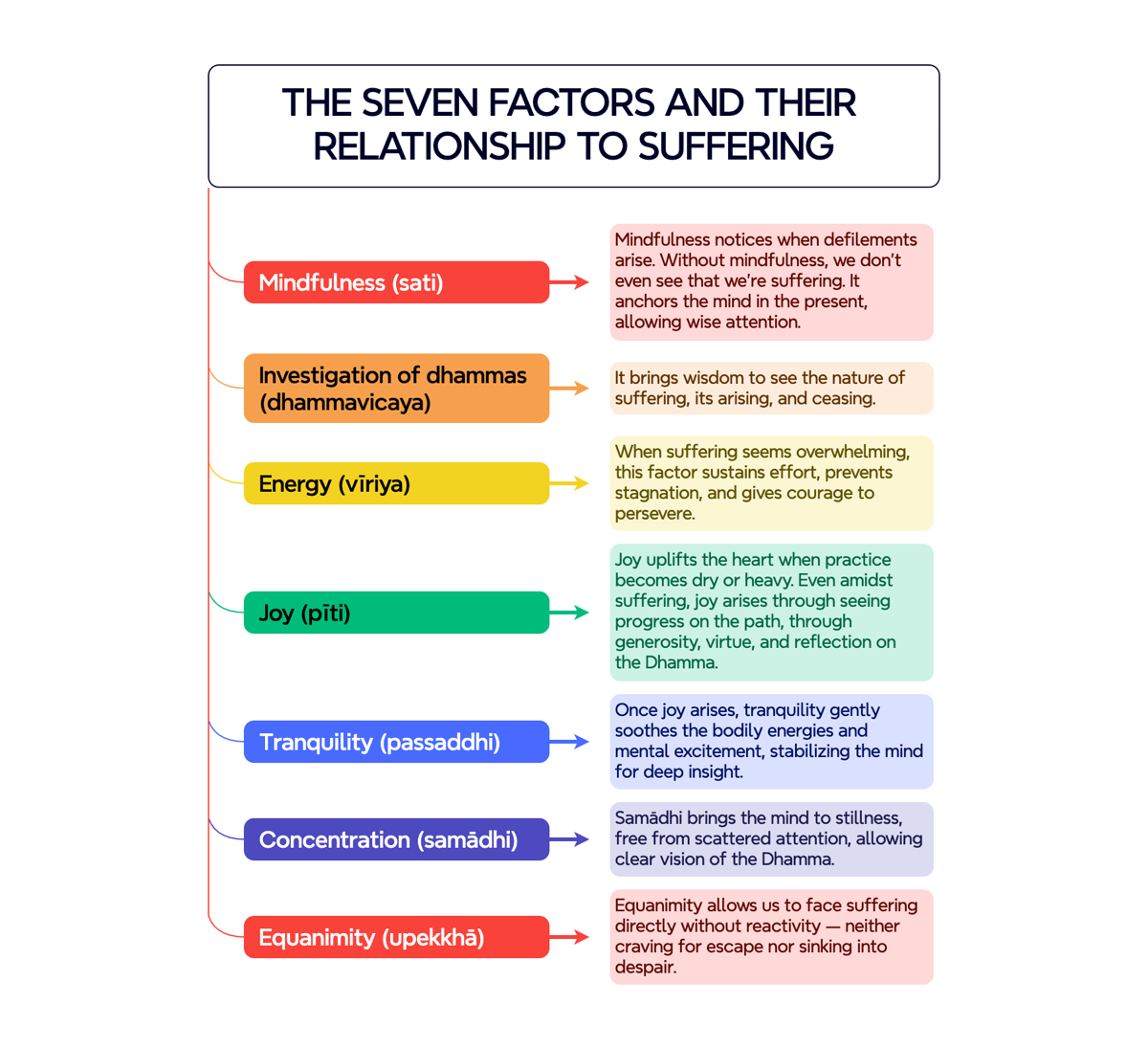

At this stage of the Gradual Training, we abandon the hindrances through the cultivation of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. These factors serve to balance and purify the mind, allowing it to perceive and penetrate all phenomena with wisdom and equanimity.

When fully developed, the Seven Factors of Enlightenment lead to nibbāna, the complete knowing and eradication of suffering.

The Five Hindrances

Let’s begin with a brief overview of the Five Hindrances:

-

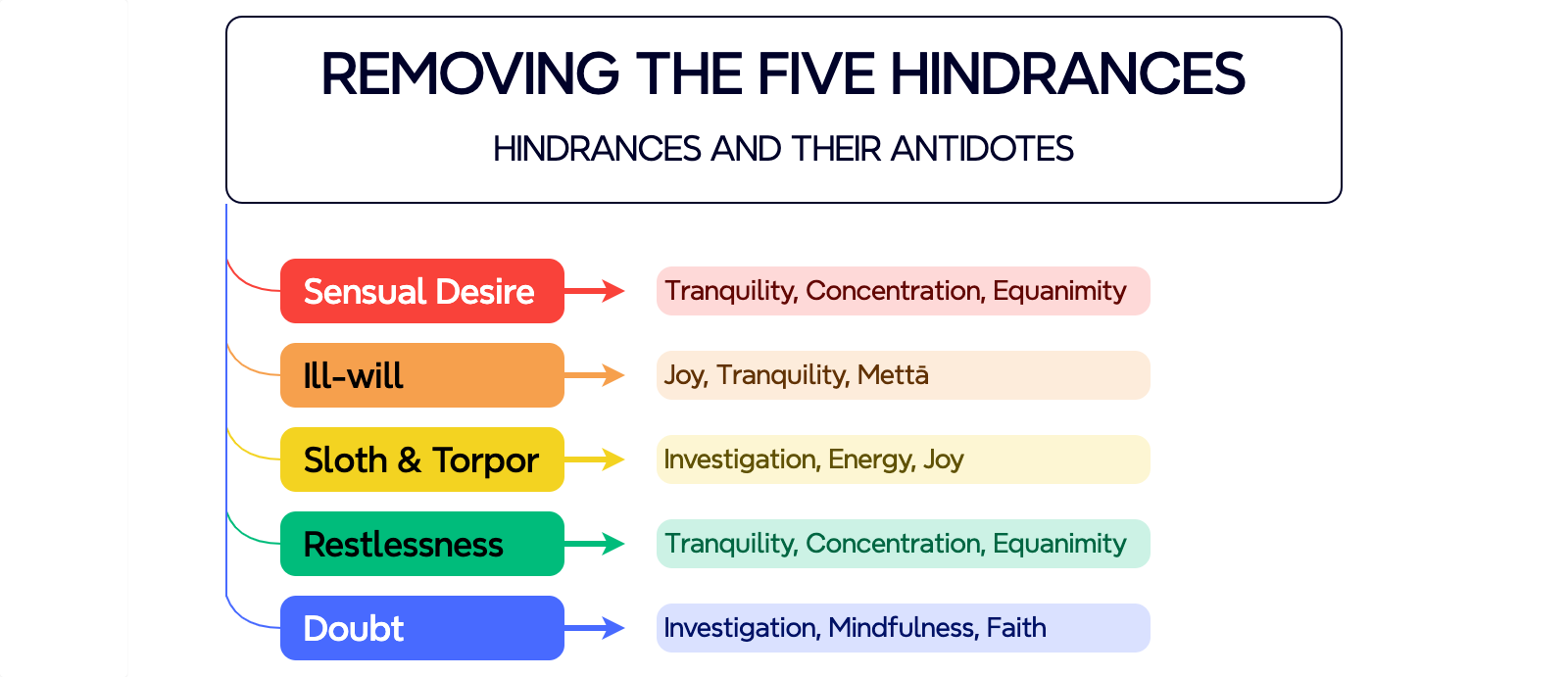

Sensual Desire: This is the craving for sensual gratification and clinging to pleasurable sensory experiences, sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and physical sensations. The mind becomes entangled in longing and attachment.

-

Ill-Will: This refers to aversion in its many forms, hostility, resentment, irritation, or anger—directed toward ourselves, others, situations, or states of being.

-

Sloth and Torpor: Sloth is a dullness or sluggishness of mind, while torpor is both physical and mental inertia, manifesting as drowsiness, heaviness, or a lack of energy.

-

Restlessness and Worry: This is a state of mental agitation, where the mind is unsettled by anxiety, regret, or unease. It involves being preoccupied with past or future events, which prevents inner stillness.

-

Doubt: This is the wavering of the mind—skepticism, indecision, or lack of confidence in the teachings, in the path, or in one’s own capacity to practice and awaken.

Despite their differences, all five hindrances share a common root: they arise from desire, aversion, or delusion. In each case, the mind reacts to experience by craving pleasure, pushing away discomfort, or distracting itself from the present moment. This reactivity disrupts mindfulness and weakens concentration, obscuring the clarity needed for insight.

The Five Hindrances: The Gradual Training

As we progress through the stages of the Gradual Training, we address these hindrances in a gradual manner. At each stage, we cultivate new skills and practices to overcome the remaining hindrances.

The Practice of Sila: We let go of desire, aversion, and attachment in interactions by practicing Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood. We renounce expectations, assumptions, and taking others for granted. We avoid harmful interactions that disturb the mind and cultivate goodwill toward everyone.

Guarding the Sense Doors: We learn to avoid entanglement by not clinging to sensory signs that provoke greed, aversion, or delusion.

Moderation in Eating: We practice moderation in eating and resist delighting in or craving flavors and food.

The Practice of Wakefulness: We maintain a clear mind by not getting lost in unwholesome thoughts.

Right Mindfulness: We abide in one of the Four Dwellings of Mindfulness, subduing greed and aversion for the "world."

At this stage of the Gradual Training, the Five Hindrances should no longer manifest as overt actions or speech. Instead, they may arise as residual forces, subtle karmic momentum, or background tendencies.

As we continue in our practice, we become more sensitive to the underlying causes of suffering. We can start to detect these roots within ourselves, rather than just reacting to symptoms.

For example, sensual desire might not manifest as seeking gross physical gratification anymore, but it could still be manifesting in subtle ways. We might find ourselves clinging to certain perceptions or expectations, like attachment to our bodies or a need for everything to go smoothly.

Ill-will can also show up in more nuanced forms. Instead of anger, it might appear as aversion towards discomfort that's still present within us. We might feel a quiet urge to eliminate these residual feelings, rather than facing them directly.

Doubt can manifest similarly, not as a clear-cut uncertainty, but as a subtle questioning about our progress or the unfolding of events.

What all these manifestations share is a common thread: reactivity. When we're driven by desire, aversion, or delusion, our minds tend to lean towards seeking pleasure, avoiding discomfort, or distracting ourselves from the present moment. This reactivity can disrupt our mindfulness and undermine our concentration.

The Five Hindrances: The Stages of Liberation

As we continue on the path to liberation, it's worth noting that the Five Hindrances can't be completely eliminated until we reach a stage of liberation. But with each step forward, we can weaken and overcome them enough to abide in jhāna.

As we progress through levels of liberation, some of the hindrances are permanently eliminated:

-

At the initial stage of liberation, Stream-entry, doubt is finally eliminated. We've got a clearer understanding of the path and our own abilities.

-

By the third stage, Non-returner, sensual desire, ill-will, and remorse are gone for good. These negative tendencies no longer hold us back.

-

And at Arahatship, the highest level of liberation, sloth and torpor, as well as restlessness, are completely eradicated.

Therefore, every step taken in weakening these hindrances brings us closer to liberation, where freedom from them becomes unshakable.

A person who has completely destroyed the taints, or mental intoxicants (āsava), sensual desire, existence, views, and ignorance, has developed and well-developed the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. This person is called an arahant, a fully enlightened being.

Purifying the Mind: The Cessation of Craving

Disciples, the path that leads to the cessation of craving, that path should be developed. What is that path? It is the seven factors of enlightenment...

How, venerable sir, are the seven factors of enlightenment developed, and how do they lead to the cessation of craving?

Here, Udāyi, a disciple develops the factor of mindfulness, which is based on seclusion, dispassion, cessation, and the relinquishing of attachment. As he develops the factor of mindfulness, which is based on seclusion, dispassion, cessation, and the relinquishing of attachment, craving is abandoned. When craving ceases, volitional fabrication ceases; With the abandonment of volitional fabrication, suffering ceases.

SN46.26

It’s crucial to remember that the aim of the Gradual Training is to establish the causes and conditions that lead to the cessation of craving: craving sense satisfaction, craving becoming, and craving non-becoming. This requires a purified mind capable of penetrating the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and non-self nature of experience. Only then can dispassion emerge, which, when cultivated, leads to seeing the gradual fading away, cessation, and ultimately the release of all craving.

The mind must be purified so that it is clear, concentrated, unshakable, free from entanglement, imbued with the single-minded intention of destroying the taints.

To create the causes and conditions for such a mind requires developing the Seven Factors of Enlightenment.

Conditions for the Cessation of Craving

When the Tathagata spoke of practice “based on seclusion, dispassion, cessation, and relinquishment,” he was describing the conditions that lead to liberation — a freedom from the pressures of desire and the quieting of craving

-

Seclusion: withdrawing the mind from the pull of the senses and the noise of conceptual proliferation. In seclusion, the mind no longer feeds on the "world"; it abides independently.

-

Dispassion: the fading of lust, of “I want.” Where the fire of passion cools, perception becomes clear and unentangled.

-

Cessation: recognizing that every arising experience fades when its cause fades. Seeing this directly undermines attachment to continuity, trying to make experience lasting or permanent.

-

Relinquishment: the deliberate letting go of ownership and self-reference. The mind releases even its clinging to wholesome states, finding stillness in non-clinging.

When the practice of mindfulness and other wholesome factors is rooted in these four supports, it does not generate new becoming, it leads instead toward tranquility.

The Unbinding of Craving

Craving is the binding thread that holds the entire fabric of becoming together. It arises through the delight in feeling, the subtle insistence that “this must stay,” or “this must change.”

When mindfulness is infused with dispassion and relinquishment, it sees craving not as “my desire,” but as an impersonal process: a movement of energy arising and ceasing according to conditions. This clear seeing dissolves the enchantment.

Clinging cannot survive in a mind that neither craves nor resists what arises. The mind that abides in seclusion and dispassion simply knows without doing, it is awareness unobstructed by wanting.

The Fading of Volitional Activity

When craving ceases, the energy that fuels volition dries up. The mind still functions, perceiving, thinking, moving, but it no longer fabricates a self who acts. This is the stillness of a liberated mind: movement without karmic accumulation, responsiveness without ownership.

The Cessation of Suffering

When volitional constructing ceases, the wheel of dependent origination loses its hub. Without craving, there is no clinging; without clinging, no becoming; without becoming, no birth; and thus no suffering.

This is not annihilation, but the exhaustion of the self-making process, the cooling of the fires of “I” and “mine.” The Tathagata called this the "nibbāna-dhātu", the element of stillness, where nothing more is built upon experience.

From Conditioned Practice to Unconditioned Stillness

Thus, the Seven Factors of Enlightenment are not separate attainments, but the refinement of conditions that allow craving to end. When they are cultivated based on seclusion, dispassion, cessation, and relinquishment, they mature toward liberation by their nature.

The factors don't "do" the freeing, they ripen into liberation, because their roots no longer feed on becoming. Mindfulness becomes the gatekeeper of release: clear, steady, dispassionate, and unbound.

The Tathāgata compares the abandoning of the Five Hindrances to the process of purifying gold. Just as a goldsmith removes impurities, like iron, copper, tin, and lead, from raw gold through repeated smelting and refining, so too does a disciple remove sensual desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and remorse, and doubt through diligent practice.

As the impurities vanish, the mind becomes bright, malleable, and ready for work, just as purified gold is fit for crafting exquisite ornaments. In this purified state, the mind can penetrate higher wisdom for the destruction of the taints.

Disciples, these five impurities of gold, which when present in gold, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly come to fulfillment in any craftsmanship. What are the five?

Iron, copper, tin, lead, and silver: these are the five impurities of gold, which when present in gold, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly come to fulfillment in any craftsmanship.

But when gold is freed from these five impurities, it becomes pliable, workable, and radiant; it is not brittle and properly comes to fulfillment in any craftsmanship. Whatever ornament one wishes to make from it: whether a ring, earrings, a necklace, or a golden chain: it serves that purpose.

Similarly, these are the five impurities of the mind, which when present in the mind, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly attain concentration for the destruction of the taints. What are the five?

Sensual desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and worry, and doubt: these are the five impurities of the mind, which when present in the mind, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly attain concentration for the destruction of the taints.

But when the mind is freed from these five impurities, it becomes pliable, workable, and radiant; it is not brittle and properly attains concentration for the destruction of the taints.

AN5.23

Before we dive into how to use the Seven Factors of Enlightenment to overcome the Five Hindrances, it's important to first understand what we’re trying to purify. This requires learning some basic concepts about the mind stream and what the Tathāgata calls “mental formations.”

Purifying the Mind: Karmic Energy

To understand the practice of Abandoning the Five Hindrances, it's useful to see the hindrances as manifestations of karmic energy.

Karma, is essentially a form of mental energy. It possesses both momentum and volition, and it's deeply rooted in our past desires. These desires then manifest as intentions to fulfill those very desires.

This mental energy, which carries power behind it, is what drives our fundamental desire for existence itself. It's what creates the sense of "being," and importantly, the desire to take birth in a physical body, all in order to seek satisfaction out in the world. And this desire, in turn, manifests through our bodily, mental, and verbal actions, what the Tathāgata refers to as bodily, mental, and verbal formations.

Since karma is rooted in greed, aversion, and delusion, it shows up in the present moment as a restless, scattered mental energy. It's constantly seeking satisfaction, always seeking to "feed" on the objects of the world, which is what we call craving for sense satisfaction. This continual seeking and the underlying restlessness it causes, result in a mind that's tainted and disturbed, clouded by ignorance, and ultimately, incapable of achieving liberation.

As we progress on the Gradual Training and develop the Eightfold Path, that scattered mental energy begins to diminish. This leads to a mind that's more collected and settled, now singularly focused on liberation.

However, even at this stage of the Gradual Training, restlessness still remains. It's like a constant stream of ingrained karmic mental energy, still seeking an outlet through the desire for existence, clinging to the Five Aggregates.

This unsettled mental energy is what the Tathāgata refers to as the "five impurities of the mind." When these are present, the mind becomes neither pliable, workable, nor radiant. Consequently, it can't properly attain the concentration needed for the destruction of the taints.

Therefore, to truly progress on the path to liberation, we must transform this impure and scattered mental energy by cultivating the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. Through this practice, the mind becomes purified into a steady stream of pliant, collected energy, unified and intent on the destruction of the taints.

But, disciples, when the mind is freed from these five impurities, it becomes pliable, workable, and radiant; it is not brittle and properly attains concentration for the destruction of the taints.

AN5.23

Purifying the Mind: Purifying New Karma

To truly understand what it means to purify the mind, we need to reflect on a core teaching of the Tathāgata: The mind is the forerunner of all experience.

It is not that things simply exist, and the mind perceives them exactly as they are. Rather, the ordinary mind, driven by tainted karmic intentions, is constantly seeking, constantly selecting what to pay attention to. And in doing so, perception becomes stained, colored by craving, craving to hold on to what feels good, and escape what feels unpleasant.

So what does this really mean? It means that experience doesn’t just happen to us. The mind creates it, through what it intends, what it pays attention to, and how it interprets what it perceives.

Yes, things exist just as they are. But whether we see them as good or bad is shaped by our inner tendencies, our desires, our intentions. These reactions produce formations, mental, bodily, and verbal, that shape our entire experience, all under the influence of greed, aversion, and delusion.

To appreciate this important point, consider this: intention is the builder of karma. The moment the mind leans, even subtly, toward a particular act, karma is already beginning to form. The stronger the volition, the more significant its impact, shaping future actions when the right conditions come together.

But karma doesn’t just show itself in what we do. It’s also embedded in the most subtle shifts in perception, in the energy behind how we choose, what we believe, how we see ourselves. Even the tiniest moment of craving, aversion, or delusion carries karmic weight.

At this stage of the Gradual Training, the focus is on purifying the mind by letting go of unwholesome mental states, the Five Hindrances, and instead cultivating wholesome ones, the Seven Factors of Enlightenment.

This means purifying our views, intentions, inner speech, and actions, how we practice, strive, pay attention, and ultimately perceive the “world”, all gathered into a single, collected stream of mental energy intent on the destruction of the taints.

Purifying the Mind: The Eight Fold Path

At this stage of the Gradual Training, in order to purify the mind, we need to shift how we see the Eightfold Path. No longer do we see the Eightfold Path as separate components of the Tathāgata's teaching. Instead, we recognize it as a single, unified force, for purification, steadily leading the mind toward liberation.

We engage with all eight factors of the path as one integrated whole. Every practice we undertake, every moment of contemplation, must now be infused with the essence of the Eightfold Path.

Right View

This is where everything begins, clear seeing. It’s the foundation beneath our practice. Right View is perceiving impermanence in all things, stress in clinging, and the truth of non-self in each experience. Every mental state becomes a doorway, an invitation to see with clarity, free from distortion. Our aim now is to purify how we see the world, how we construct meaning, and to glimpse the path of liberation.

Right Intention

Alongside clear seeing, we turn the mind toward renunciation, Right Intention. But here, we deepen our sensitivity, not just to our outward choices, but to the subtle energies driving those choices. Every mental impulse becomes a question: “Is this arising from craving, aversion, or delusion? Or from letting go, goodwill, and wisdom?”

Because intention is the fuel behind karma and mental formations, Right View and Right Intention together form the wisdom wing of the path, steering the mind toward freedom.

Whatever one frequently thinks and ponders upon, that will become the inclination of the mind.

MN19

Right Speech

In the same way, we must learn to recognize the earliest stirrings of speech—our initial thoughts, silent formulations, and inner dialogues. At this stage, “speech” is not merely what is spoken aloud, but what first arises in the mind. These subtle seeds, such as “this is good,” “this is bad,” or “I want”, form the ground for either delusion or wisdom. Rather than using inner speech to label or judge, we learn to use it skillfully: as directed thought and reflection, and more subtly, as directed and sustained attention that supports the path of letting go.

Right Action

No longer just a matter of behavior, action now refers to the internal movements of the mind. How does the mind respond to feelings, perceptions, and thoughts? Do we tighten or soften? Cling or release? Resist or open? Moment by moment, action becomes the art of renunciation, the practice of releasing, again and again.

Right Livelihood

Livelihood, at this stage in the Gradual Training, is not about profession, it is about living the path. Our way of life becomes the Eightfold Path itself. Right Livelihood is now the internal and external orientation to the Dharma, our sole foundation for being in the world.

Right Effort

Effort becomes effortless. With continuous practice, the Four Right Efforts, preventing, abandoning, cultivating, and maintaining, merge into one flowing application of the mind. Eventually, there’s no sense of struggle, no doer. Just the unfolding of karmic energy gently moving toward release.

Right Mindfulness

We are no longer “trying” to be mindful. Instead, mindfulness arises naturally, as abiding in presence, and contemplation, steady and uninterrupted. Not through an act of will, but as a steady presence. We are no longer trying to be mindful; instead, mindfulness becomes the seamless thread that binds all other factors together.

Right Concentration

And finally, when all these factors settle and strengthen, when the hindrances fade and the Seven Factors of Enlightenment begin to arise, Right Concentration naturally emerges. The mind becomes unified, collected, and capable of seeing things as they truly are.

At this point, the Eightfold Path ceases to be a conceptual framework. It becomes the path itself, a single, stream of mental energy, moving toward the complete uprooting of the taints.

Purifying the Mind: Understanding Mental Formations

At this stage of the Gradual Training, we begin to understand something profound: applying the Eightfold Path isn’t just following steps, it’s a process of purification. It’s the cleansing of karma and the transformation of the mind stream itself. What we’re really doing is shifting the inner causes and conditions that shape a tainted mind into a purified one.

But to fully appreciate how this works, and how the Eightfold Path operates, we need to look more closely at Mental Formations.

Mental Formations are the hidden architects behind every experience we have. They aren’t just the obvious intentions or deliberate choices we make. They also include the subtle leanings of the mind, its reactions to what arises, the emotional coloring we bring to moments, and even the deep, rooted habits that guide how we respond. These formations are constantly at work, quietly shaping our consciousness, our actions, and our future experiences.

At its core, clear knowing arises through intention, attention, and perception, all dependent on contact and feeling. Whatever arises beyond this is fabrication.

The Tathāgata often pointed to these five aspects as the direct way to cut through fabrication. In practice, when we rest with bare attention on contact, feeling, perception, and intention, without weaving stories around them, we experience reality before it is fabricated. This is "knowing".

Thoughts, beliefs, identities, and narratives arise within this bare knowing. While they have their place for our functioning, when clung to as self or truth, they give rise to confusion and suffering.

In essence, Mental Formations are how the mind constructs our experience of reality. Yes, our actions are intentional, but they don’t spring from a solid, unchanging self. Instead, they emerge from a vast, interdependent web of causes and conditions. And to truly grasp this, not just intellectually, is to unravel the very core of self-view and open the path to liberation.

So understanding Mental Formations is absolutely crucial. We need to see how they emerge, how they operate just beneath conscious awareness, and how, through insight, they can begin to dissolve.

Merely thinking about Mental Formations won’t set us free. We need direct experience. We need to observe them, trace them back to the views that give rise to them, and recognize their true nature: impermanent, not-self, conditioned. When we begin to see this clearly, again and again, the grip of saṁsāra starts to loosen.

Mental Formations: Shaped by Views

To truly understand the Five Hindrances, and how they can be purified, we must look deeper than their surface manifestations. At their root lies something more subtle and powerful: our views. Not just intellectual beliefs, but deeply ingrained assumptions that shape how we perceive reality.

The mind interprets experience through these lenses: I exist, this is mine, I am this body, I am the experiencer, I must be happy, I must be free of pain. These aren’t harmless abstractions. They’re deeply held views, built on ignorance, that give rise to craving, aversion, restlessness, sloth, and doubt.

Letting go of wrong views begins the process of dismantling the architecture that holds the hindrances together. Take, for example, the view “I am this body.” As long as this view persists, physical discomfort becomes personal suffering. Every ache, illness, or wrinkle feels threatening, because they affect “me.” The body ceases to be seen as a changing, impersonal process, and becomes a fragile possession. And so we cling: to youth, to comfort, to survival.

These feelings, in turn, give rise to Mental Formations. The mind begins to seek, control, preserve, beautify, fear, or avoid anything that threatens this core view, all to protect the fragile illusion of self. These reactions seem natural, but they’re fabrications, karmic echoes arising from misperception. It is the view that activates these formations; without the view, the suffering loses its foundation.

The big challenge is that the most powerful views aren’t always obvious. Often, we don’t know we’re holding them. They’re assumptions masquerading as truth, quietly running the show behind the scenes. When we don’t examine them, Mental Formations stay hidden, subtly steering our choices, shaping our karma.

Freedom begins when we shine light into that hidden machinery. When we question the unquestioned, and when we no longer mistake views for reality.

Mental Formations: Craving and Intention

From our deeply rooted views, craving arises. And with craving come fear, clinging, identification, and the intention to act in order to fulfill those cravings.

Mental formations often arise subtly. Think of them as quiet shifts in the mind: a slight leaning toward something pleasant, a tension in the body when an old memory surfaces, a silent replay of a past conversation, or a subtle longing to be seen in a certain way.

These have not yet manifested into overt actions, but they carry momentum. They are the early ripples, subtle, but powerful, that set the current of suffering in motion.

When we see these mental formations with full mindfulness, supported by wisdom, something begins to change. We start to notice:

-

“Ah, this impulse, it’s coming from fear.”

-

“This reaction, it's rooted in the view ‘I am this.’”

-

“This quiet anger, it’s rising from the sense of having been wronged.”

We don't reject these movements, and we don't chase them. We observe them, gently, clearly, tracing them back to the conditions they arose from. And as our seeing becomes clearer, something profound begins to happen: dispassion emerges. These formations lose their grip, their energy fades, and what once drove us begins to dissolve.

Using wise attention, we pause and reflect:

-

A thought has appeared, what was its origin?

-

An impulse arose, what set it in motion?

-

Anger surfaced, what contact lit the flame?

Instead of saying, “I am angry,” we begin to say, “Anger has arisen, conditioned by contact, shaped by perception, memory, and habit.”

Seeing clearly in this way, we begin to loosen our grip on the identity wrapped around the feeling, and through this kind of insight, something subtle yet transformative is revealed: yes, our actions are intentional, but they’re not owned. They don’t come from a permanent self. They rise from a vast web of conditions, dynamic, interwoven, and ever-changing.

When we see this, not just with the mind, but through direct experience, the whole engine of clinging begins to loosen. This understanding isn’t conceptual, it has to be known, felt, seen, with clarity, with depth, and with the courage to let go.

Mental Formations: Intention, Attention, Perception, and Effort

If wanderers of other sects were to ask you, On what are all things rooted, friends? From what do all things arise? Where do all things originate? Where do all things converge? What is the foremost of all things? What is the ruler of all things? What is the highest of all things? What is the essence of all things? What is the immersion of all things? What is the culmination of all things?

Being asked thus you should answer those wanderers of other sects in this way: All things are rooted in desire, friends. All things arise from attention. All things originate from contact. All things converge in feeling. Concentration is the foremost of all things. Mindfulness is the ruler of all things. Wisdom is the highest of all things. Liberation is the essence of all things. The deathless is the immersion of all things. Nibbāna is the culmination of all things.

AN10.58

So, as we’ve just explored, letting go of the Five Hindrances and nurturing the Seven Factors of Enlightenment calls for a deeper, more refined awareness, a way of seeing that recognizes intention, attention, perception, and effort as subtle movements of the mind.

Just as a goldsmith carefully applies intention, attention, and effort to separate impurities from gold, making it pliable and ready to be shaped into something beautiful. In the same way, we must continue cultivating Right View, Right Intention, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Investigation, refining the mind and its perceptions in pursuit of true clarity, and ultimately, the destruction of the taints.

Intention: The Sign of the Mind

Recognizing our intentions, even in their quietest, most subtle forms, is vital. Why is that? Because intention shapes what we pay attention to, how we perceive reality, and the overall tone and quality of our efforts.

To work skillfully with this, we must become attuned to what the Tathāgata referred to as the sign of the mind. The sign of the mind is the mental impression, the feeling tone, or subtle inclination that the mind picks up and begins to lean toward. This “sign” isn’t always something we can picture, sometimes, it’s a faint flavor, a subtle emotional charge or a barely noticeable tug in a particular direction.

Yet even these subtle cues condition how our perception unfolds, and how karma begins to stir. As stated in DN 22:

A disciple knows a mind with lust as a mind with lust, a mind without lust as a mind without lust; a mind with hatred as a mind with hatred, a mind without hatred as a mind without hatred; a mind with delusion as a mind with delusion, a mind without delusion as a mind without delusion...

DN22

The “sign of the mind” is more than a passing impression. It’s the seed of intention. Even before thought fully forms, if there’s a leaning, a preference, a subtle emotional tone, that sign quietly reveals the mind’s direction.

And if we miss it, if it goes unnoticed, it becomes fertile ground for craving, and gives rise to mental proliferation. So when we refer to “the sign of the mind,” we’re pointing to the object or quality the mind is tuned into.

Sometimes, it’s lust, sometimes irritation and sometimes renunciation.

It’s the tone beneath the surface, the leaning that exposes the mind’s tendency. From that seed, thought arises, habit takes shape, and proliferation takes hold. Recognizing this sign, clearly and early, gives us an extraordinary opportunity: to stop the wheel of becoming before it even begins to turn.

So although there may be an intention for lust, we still have the choice in how to respond, whether to go along with it, redirect it to the wholesome or skillful, or let it pass.

That’s why when the Tathāgata taught the Abandoning of the Five Hindrances and the Cultivation of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, he wasn’t offering two separate instructions. He was pointing to one integrated path, a single process: purifying the sign of the mind, refining the inclination it rests on, and when that sign is clear, wholesome, and settled, the path unfolds on its own.

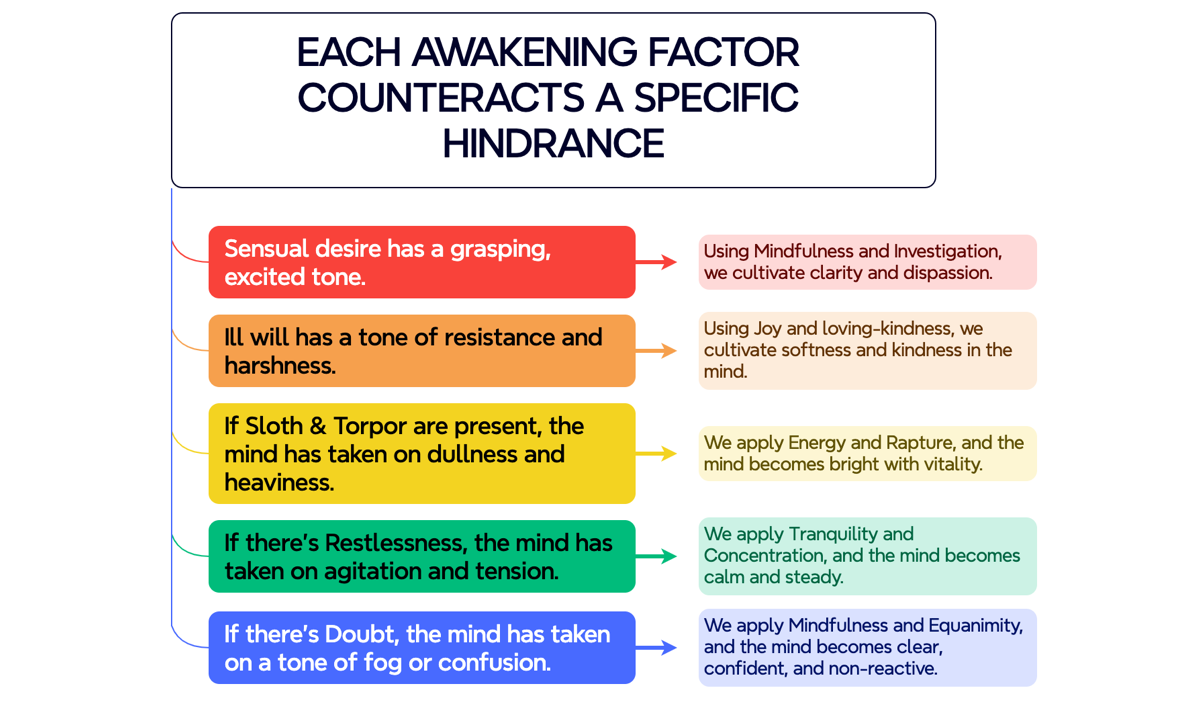

Each Enlightenment Factor Counteracts a Specific Hindrance

In the cultivation of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, each Enlightenment Factor serves to counteract a specific mental inclination, one born from the hindrances. It does this by shifting the sign of the mind toward clarity and tranquility.

For example:

-

Sensual desire carries a craving, excited energy. Through Mindfulness and Investigation, we invite clarity and dispassion.

-

Ill will has the flavor of resistance, of harshness. We meet it with Joy and Loving-kindness, and the mind begins to soften and open.

-

Sloth and torpor weigh the mind down, dull and heavy. By applying Energy and Rapture, vitality returns and the mind brightens.

-

Restlessness feels like tension, agitation. With Tranquility and Concentration, we steady the mind, allowing it to settle like still water.

-

And when Doubt clouds perception, we bring forward Mindfulness and Equanimity, and the fog begins to clear, confidence replaces confusion and presence replaces uncertainty.

This practice isn’t about battling the hindrances. It’s about meeting each one with skillful means: changing the mind’s inclination.

When you notice restlessness, instead of fighting it, simply acknowledge it, “Ah, my mind is leaning towards anxiety and a sense of incompleteness.” Then, gently redirect your attention to a tranquil sign, such as your breath, your body, or a perception that provides stillness, and restlessness gradually loses its footing.

This practice isn’t about eliminating all mental movement. It’s about knowing the texture of each movement, not identifying with it, not feeding it, but releasing it.

Rather than reinforcing the Five Hindrances, we retrain the mind to rest upon the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, and in doing so, the mind is purified, not superficially, but at the root.

Also, this is key, when we notice the mind’s inclination, what we’re seeing is old karma. And when we understand that, we stop blaming the world for what appears. We stop blaming ourselves for what arises. Instead, we see clearly: “This is old karma playing out,” and in that seeing, we take full responsibility, not for what arises, but for what we do next, how we respond to the sign of the mind.

Mental Formations: Attention

The result of intention is attention.

Attention directs the stream of consciousness. Attention is intentional, an act of will directed toward perception, like turning toward the breath, or resting in a single sensation.

Attention comes before perception, without it, perception cannot arise. Perception requires contact, but it is attention that points the mind toward contact. It’s the silent cue, the unseen gesture that says: “Look here,” and what the mind looks at, matters.

Attention is not passive; it actively shapes experience. Whatever we give attention to grows. This means the mind can be purified by how it pays attention and what it pays attention to. By ceasing to nurture unwholesome perceptions and instead directing attention to what is wholesome, the mind begins to clarify, brighten, and unify.

Intention is the energy that gives rise to mental formations. Attention is the channel through which this energy flows into the world, facilitating the meeting of consciousness and experience. The type of attention, the objects it touches, and the activities it engages in all contribute to the unfolding of karmic consequences.

Attention can be wholesome or unwholesome. Wise attention is guided by Right View, it brings disenchantment, dispassion, and release.

Unwise attention clings, it proliferates thought, feeds craving, cements views, and builds bondage.

Attention: From Ordinary to Supramundane

In the Tathagata’s teaching, the movement from the mundane to the supramundane path is not a leap between two worlds, it is a refinement of how the mind attends. What we call “attention” is not neutral; it is an energetic act, a conditioning movement of mind. Each time attention lands on an object, it initiates a subtle chain of formations, including verbal fabrications.

Understanding this is central to the Gradual Training, because as long as attention is active, fabrication is active. How this fabrication manifests depends on the refinement of the mind. Let us look at this in three stages: the ordinary person, the practitioner, and the noble disciple.

The Ordinary Person: Attention as Self-Chatter

For the ordinary, untrained mind, attention naturally gives rise to a stream of verbalization. When attention moves toward a sight, sound, memory, or feeling, it instantly sparks self-referential thinking, commentary, evaluation, preference.

This is the habitual “inner voice” or self-chatter. It’s the constant narration that follows attention like a shadow: “I like this.” “I shouldn’t have said that.” “What will happen next?”

Each moment of attention becomes a seed for further proliferation. Because the mind identifies with attention, “I am the one who attends”, it generates thought after thought to sustain the illusion of a continuous self.

In Pāli, vitakka and vicāra describe this energetic process: vitakka directs attention, vicāra sustains it. Together they keep the self-story alive through verbal fabrication.

The Practitioner: Attention as Skillful Guidance

For the one walking the mundane path, the earnest practitioner, attention becomes more disciplined. Through mindfulness and right effort, the coarse chatter quiets down. Yet some verbal fabrication remains, though now it serves Dhamma rather than delusion.

The practitioner still employs vitakka and vicāra, but in a refined, wholesome way. For instance: “Stay with the breath.” “Soften the effort.” “Observe with kindness.”

These are not strong inner speeches but soft, almost vibrational thoughts, subtle verbal movements that orient awareness toward skillful qualities. They are verbal fabrications to aid Right Mindfulness.

This is the level described in the first jhāna:

Quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, a disciple enters and dwells in the first jhāna, which is accompanied by directed and sustained attention, with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion.

DN2

Here, attention is unified and wholesome, but it still fabricates, there is still refined inner speech, even as subtle as proto-toughts. The mind still adds self-referencing, when it directs and sustains attention, though purified, is still a doing, still a formation.

The Noble Disciple: Attention as Letting Go

For the noble disciple walking the supramundane path, he knows that even attention is an act of clinging. When this is seen directly, and through practice, the energy of attention no longer needs to hold, direct, or sustain. Awareness begins to rest in itself. Vitakka and vicāra fall away, not suppressed, but naturally stilled.

This is expressed in the second jhāna, where the Tathagata says:

With the stilling of directed and sustained attention, he enters and dwells in the second jhāna, which has internal confidence and unification of mind, without directed and sustained attention.

DN2

At this stage of Right Concentration, verbal fabrication ceases. The mind no longer murmurs instructions to itself, nor holds attention as an object. The subtle sense of “I who attends” dissolves. Awareness becomes effortless, and seeing simply knows.

This is why dwelling in jhāna is essential for direct knowing without fabrication.

This is also the stilling of the mental formations aggregate. The noble disciple’s mindfulness is no longer fabricated; it is direct knowing, free from verbal mediation.

In MN 118 (Ānāpānasati Sutta), the Tathagata gives explicit instructions as part of mindfulness training:

He trains thus: ‘I will calm bodily fabrication.’ He trains thus: ‘I will calm mental fabrication.’

DN2

Here, “calming mental fabrication” refers to the cessation of vitakka-vicāra, attention’s verbal component. This is direct seeing without the echo of thought.

The Energetic Nature of Pāli Terms

Since there is a lot of misunderstanding regarding the use of thought or attention, it is essential to understand that in Pāli, these terms: vitakka, vicāra, saṅkhāra, are not static nouns. They describe energetic tendencies, causal processes.

-

Vitakka is the energy of initial placing, the moment attention “strikes” an object.

-

Vicāra is the energy of continued contact, the mental vibration that holds the object in awareness.

-

Vacī-saṅkhāra is the energetic verbal fabrications produced by this contact, the proto-thoughts, subtle chatter or full-blown verbal fabrications that sustain knowing as “mine.”

When these energies are purified, attention transforms from an act of possession to a quality of release. What was once “I am attending” becomes simply there is knowing.

Therefore, “directed and sustained attention” is not a mere technical detail of the practice. It is a deep truth about how mind fabricates experience through attention. Therefore, training attention is the core of the practice.

Attention: What One Pays Attention to Grows

The Tathāgata teaches us that whatever we place attention on grows. The mind is nourished by what it dwells upon, whether wholesome or unwholesome. If attention is habitually given to greed, aversion, or delusion, these roots deepen. But when attention is turned toward tranquility and wisdom, these wholesome qualities expand and strengthen.

To purify the mind, we need to use Right Effort to cultivate two key attentional skills:

-

Vitakka, the initial application of attention. It is the turning of the mind away from an unwholesome object toward a wholesome one.

-

Vicāra, sustained attention. It maintains contact with the chosen object, investigates it, stays with it, and steadies presence there.

Just as a skilled bathman mixes bath powder with water into a smooth lather... so too a disciple drenches his body with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion...

AN5.28

In this simile, the Tathāgata shows how vitakka and vicāra function together as the gentle movements of directed and sustained attention. Like the bathman carefully blending powder and water, these two mental activities shape the mind into a unified experience of joy and tranquility born of seclusion.

When we intentionally direct the mind (vitakka) and sustain it (vicāra) upon a particular perception, such as “this is impermanent,” “this is empty of self,” “this is unsatisfactory”, we are training the mind to return again and again to the liberating characteristics of experience. Over time, this repeated turning and sustaining forms a wholesome habit, inclining the mind naturally toward insight and release.

This is how Right Effort is developed: we deliberately direct attention toward the wholesome and keep it there, nurturing what leads to peace and letting the unwholesome wither through neglect.

Thus, purifying attention is the cultivation of a purified mind-stream, one that flows with clarity, steadiness, and wisdom. As this current strengthens, it naturally carries us toward deep concentration, and from there, into direct insight.

Attention: Wise Attention

Not understanding what things are fit for attention and what things are unfit for attention, he attends to things unfit for attention and does not attend to things fit for attention.

And what are the things unfit for attention that he attends to?

Whatever things, when attended to, lead to the arising of unarisen sensual desire, or to the increase of arisen sensual desire, to the arising of unarisen desire for existence, or to the increase of arisen desire for existence, to the arising of unarisen ignorance, or to the increase of arisen ignorance: these are the things unfit for attention that he attends to.

And what are the things fit for attention that he does not attend to?

Whatever things, when attended to, do not lead to the arising of unarisen sensual desire, or to the increase of arisen sensual desire, to the arising of unarisen desire for existence, or to the increase of arisen desire for existence, to the arising of unarisen ignorance, or to the increase of arisen ignorance: these are the things fit for attention that he does not attend to.

By attending to things unfit for attention and not attending to things fit for attention, unarisen defilements arise and arisen defilements increase....

He attends wisely to: This is suffering; This is the origin of suffering; This is the cessation of suffering; This is the path leading to the cessation of suffering.

By attending wisely in this way, three fetters are abandoned: identity view, doubt, and attachment to rites and rituals.

MN2

So what is the fire that burns away karmic impurities? It is the fire of insight, and it penetrates most clearly in two modes: seeing and developing.

In MN 2, the Tathāgata describes seven methods for abandoning the taints: seeing, restraining, using, enduring, avoiding, removing, and developing, but only two lead directly to liberation, to the Supramundane path:

-

Abandoning by seeing: Always, mindfulness comes first. Clear knowing is the doorway, and often, simply seeing a hindrance, without judgment, without clinging, is enough to loosen its grip. Through Right View, we see: “This is not-self. This is impermanent. This is dukkha.” And seeing this way, wrong view begins to dissolve, we stop wrestling with shadows, we see things as they are, and the mind begins to let go.

-

Abandoning by developing: This is the active process. Here, we cultivate the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, we nourish the wholesome. Each factor: mindfulness, investigation, energy, joy, tranquility, concentration, and equanimity, becomes medicine for the mind. Through their development, the hindrances are not just suppressed, they are uprooted.

The other five methods: restraining, using, enduring, avoiding, and removing, they serve as temporary measures, skillful in moments, but not sufficient for liberation. They calm the waters, but they don’t remove the source of turbulence.

So at this point in the Gradual Training, we shift toward creating the causes and conditions for true liberation. We abide in one of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, and from there, generate the wholesome through the Seven Factors.

As every individual is different, one will need to identify which hindrances affect them the most, understand how and when they arise, recognize their inner strengths to counter each hindrance, and actively cultivate relevant practices to overcome them.

Disciples, considering the internal factor, I do not see any other single factor that is so conducive to the arising of the seven factors of enlightenment as wise attention. For a disciple who is endowed with wise attention, it is to be expected that he will develop and cultivate the seven factors of enlightenment.

And how does a disciple who is endowed with wise attention develop and cultivate the seven factors of enlightenment? Here a disciple develops the enlightenment factor of mindfulness, which is based on seclusion, dispassion, and cessation, and matures in relinquishment.

...

He develops the enlightenment factor of equanimity, which is based on seclusion, dispassion, and cessation, and matures in relinquishment.

In this way a disciple who is endowed with wise attention develops and cultivates the seven factors of enlightenment.

SN46.49

Wise Attention: Yoniso Manasikara

In the Tathāgata’s teachings, attention is not just a cognitive act, but the turning and directing of the mind toward experience. It determines how consciousness meets the world. The Tathāgata described wise attention (yoniso manasikāra) as the root of all wholesome qualities, and unwise attention (ayoniso manasikāra) as the root of all defilements.

Attention is one of the components of name in the name-and-form link of dependent origination, which includes: feeling, perception, intention, contact, and attention.

At this early point in the chain, these five functions do not yet carry the specific content of individual experiences; they are potential capacities, the interfaces or “mental equipment” that allow for the ability to feel, to recognize, to intend, to make contact, and to attend.

Later in the chain, feeling, craving, clinging, and other processes appear again, but now they function as conditioned events, arising once the mind engages with a specific contact and begins reacting to it.

In other words, before contact, attention acts like a reaching or orienting movement, the mind’s readiness for contact. It is not yet full knowing, but the preparatory turning toward knowing.

Before attention moves, there is intention. Intention directs where attention will flow, whether toward greed, aversion, or insight. Hence, wise attention is attention guided by Right Intention and Right View.

So, to develop wise attention, we need to attend directly to experience, allowing the mind to see the full chain of arising and fading of phenomena, so it can discern causes and their conditions and know the results that follow. This requires an attention that sees impermanence, suffering, and non-self. Finally, wise attention must be guided by Right View and Right Intention, and grounded in the Four Noble Truths.

With practice, wise attention becomes effortless, like a steady light illuminating phenomena without clinging. This leads the mind toward insight, dispassion, and release.

Wise Attention: The Heart of Karma and Wisdom

Among the many qualities the Tathagata praised, few shine more brightly than wise attention (yoniso manasikāra). Attention is not a “knowing” that belongs to a knower, but the way awareness turns toward experience. Every moment of consciousness depends on how it attends to its object; this mode of attending determines whether the mind moves toward delusion and craving or toward clarity and release.

When eye, ear, or mind meet their objects, there is contact. From contact arises feeling, the tone of pleasant, painful, or neutral sensation. In that same instant, perception recognizes the object, consciousness illuminates it, and attention directs the mind toward it. These factors occur together, supporting one another like the spokes of a wheel. Yet among them, it is feeling that becomes the seed from which craving can grow.

When a pleasant feeling is attended to unwisely, delight and craving arise. When a painful feeling is attended to unwisely, aversion and resistance appear. Even neutral feeling, when unnoticed, becomes the ground for ignorance. In every case, attention is the deciding factor.

When one attends unwisely, unarisen taints arise, and arisen taints increase. When one attends wisely, unarisen taints do not arise, and arisen taints are abandoned.

MN2

Thus, feeling is the root of craving, but clinging depends on the sustaining power of attention. When attention keeps circling around the object of craving, nourishing it with perception and story, craving hardens into attachment. If attention instead sees the process itself, “This is a feeling, conditioned and passing”, then craving fades and clinging cannot take hold.

This turning of attention is what shapes karma. Unwise attention rests on delusion; it constructs actions that perpetuate becoming. Wise attention rests on understanding; it fashions actions that lead to freedom. In this sense, attention is both the builder and the dissolver of karma. Through it, the mind either reinforces ignorance or awakens wisdom.

Wise attention knows causes and conditions. It sees that all phenomena arise dependent on others and have no core that can be possessed. It does not claim “I know,” but rather allows knowing to happen through seeing things as they truly are. This is how wisdom is born, not through accumulation of thought, but through direct, impersonal seeing.

To practice this is to dwell close to the roots of experience. One remains at the level of feeling and perception, attentive to their arising and ceasing, yet not carried away into proliferation. The mind observes: “pleasant,” “painful,” “neutral,” and nothing more. From such simplicity, insight deepens. The process that once led from feeling to craving and clinging now ends in understanding and tranquility.

Wise Attention: The Four Noble Truths

The Tathagata taught that liberation begins with a simple shift in how we attend. The difference between bondage and freedom is not found in the world outside, but in how attention meets experience. This is what he called wise attention, the careful, direct seeing of causes and conditions. To attend wisely means to view every arising and ceasing through the lens of the Four Noble Truths: the truth of suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the path leading to its cessation.

Seeing Suffering

Each moment of contact gives rise to feeling, pleasant, painful, or neutral. If one attends unwisely, the mind moves outward, chasing the pleasant or resisting the painful, weaving stories and identities around them. This movement itself is suffering, the unease of clinging and rejecting.

Wise attention, however, looks directly:

“This feeling, this thought, this perception—unsatisfactory, impermanent, not mine.”

This is the First Noble Truth seen not as doctrine but as direct perception. The wise mind recognizes that even the most refined pleasure contains the seed of loss. By attending this way, one stops blaming the world for dukkha and begins to understand that suffering lies in how experience is taken up, not in what experience is.

Seeing the Cause of Suffering

Craving is the origin of suffering. Yet craving does not arise automatically from feeling; it depends on how attention engages feeling. When attention is unwise, delighting in pleasure, resenting pain, ignoring neutrality, craving takes root.

Thus, the cause of suffering is not feeling itself but the way the mind attends to feeling. Here wise attention is the precise medicine: it observes the moment when feeling would become craving and simply stays at the level of direct awareness. By not feeding the fire, the process stops before it becomes burning.

To see this in real time is to know the second Noble Truth, not as belief but as direct insight.

Seeing the Cessation of Suffering

When attention no longer sustains craving, when it sees feeling clearly, without identifying, clinging, or resisting, then craving fades. As craving ceases, clinging ceases; as clinging ceases, becoming ceases; and the chain of dependent origination unravels.

This is the Third Noble Truth, the direct realization that peace arises when the mind no longer fuels its own bondage. The cessation of suffering is not something attained later; it is the non-arising of defilement in the present moment, when attention remains clear, balanced, and wise.

Seeing the Path to the Cessation

To sustain this clear mode of attention, the Tatagata taught the Noble Eightfold Path, Right View, Right Intention, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

Every factor of the path depends upon wise attention; it is the silent root beneath all the others. When Right View sees the impermanent nature of feeling, Right Effort guards the mind, Right Mindfulness observes, and Right Concentration steadies awareness, then attention naturally becomes wise. The whole path can be understood as training attention to stay aligned with the Four Noble Truths.

Wise Attention as the Living Thread

To apply the Four Noble Truths is to apply wise attention.

Wise attention is what knows causes and conditions, not as a self knowing, but as the unfolding of wisdom itself. It doesn’t say, “I understand,” but rather lets understanding arise naturally from the observation of conditionality.

In truth, there is no knower apart from attention itself; there is only this flow of seeing, feeling, and knowing conditioned by causes. But when attention becomes wise, when it contemplates all experience through the Four Noble Truths, it transforms the very ground of karma. It turns ignorance into understanding, craving into dispassion, and suffering into peace.

Thus the Four Noble Truths are not merely a doctrine to be believed; they are the living structure of wise attention itself.

Attention: Developing Concentration

At this stage of the Gradual Training, we cultivate the causes and conditions for Right Concentration. Concentration requires a mind that is not scattered, but collected, with single-minded attention.

Ordinarily, the mind is scattered, busy with many processes: thoughts, intentions, feelings, and perceptions, what the Tathāgata refers to as “formations.” In such a state, attention is divided among lingering mental processes, some hidden, awaiting the right conditions to arise.

A scattered mind does not hold multiple objects in awareness simultaneously; rather, it rapidly shifts attention from one to another, creating the illusion of multitasking. Each moment of attention is singular, but the transitions between desires, thoughts, and sensations occur so quickly that the mind feels busy and fragmented.

This restless movement is driven by underlying craving or aversion, subtly influencing where attention lands next. Instead of unified attention, the mind juggles being pulled by different objects, never fully settling. This instability gives rise to mental noise, fatigue, and a lack of clarity.

Right Concentration involves releasing these scattered formations and gathering attention into a unified, single-minded process, guided by Right Intention, with the aim of destroying the taints.

Applied to mindfulness of the body, this means collecting all attention and directing it to awareness of the body, tracking change as it happens in real time, without allowing stray thoughts or mental processes to interfere with singleness of mind.

Attention: Contact, Feeling, and Perception

Attention is the condition for contact, feeling, and perception to arise.

In the dependent origination framework, contact arises when sense organ, sense object, and attention come together.

In SN 46.2, the Tathagata includes yoniso manasikāra, wise attention, as a crucial condition for the arising of the enlightenment factors:

There are, disciples, things that are the basis for the arising of the seven factors of enlightenment.

When one gives wise attention to them, the seven factors of enlightenment arise and come to fulfillment.

SN 46.2

Attention is the "gatekeeper" of consciousness; what you attend to is what becomes real in that moment.

This is precisely why the Tathagata called attention the "chief of all mental factors" and why wise attention is said to “lead to the arising of the as-yet-unarisen wholesome qualities”.

Seclusion and narrowing of attention

In MN 20, the Tathagata teaches how the disciple gradually withdraws attention from unwholesome objects and directs it on wholesome ones, this is the beginning of purification through narrowing.

Then, in the Ānāpānasati Sutta (MN 118), mindfulness of breathing starts with attention on a single point, the breath, narrowing to a very small field of perception, one pointed, singleness of mind. Through this, the mind becomes collected, secluded from the five cords of sensual pleasure.

By narrowing the scope of attention, one creates the seclusion necessary for perception to be purified.

At first, perception is still coarse, “breath,” “body,” “light,” “joy”, but as attention stabilizes, perception becomes clear, refined, and non-conceptual.

This is why Right Concentration is defined as “the unification of mind”

Attention shapes perception, and repeated wise attention purifies it.

Expansion: The Bathman Simile (DN 2)

Once perception is purified within that narrow field, the next step is expansion, the widening of attention and the spreading of purified perception throughout the entire body and experience.

In DN 2, the Tathagata describes this spreading:

Just as a skilled bathman or his apprentice might pour bath powder into a bronze basin and sprinkle it with water, kneading it so that the ball of bath powder becomes drenched, saturated, and permeated with moisture, yet no moisture exudes from it

so too, a disciple suffuses, drenches, fills, and pervades this very body with the rapture and pleasure born of seclusion, so that there is no part of his whole body unpervaded by rapture and pleasure.

DN2

This simile shows the expansion of purified perception and feeling from a single, concentrated point to the entire body, suffused with joy (pīti) and pleasure (sukha).

In each higher jhāna, perception is further refined and expanded, not contracted. The scope widens, but the purity, established through seclusion, remains.

Perception purified by joy, tranquility, and equanimity

As one continues, the purified perception initially suffused with joy becomes suffused with tranquility and finally equanimity.

Each stage represents a different tone of perception:

-

In the first jhāna, perception is bright and joyful.

-

In the second, perception is unified and non-verbal.

-

In the third, perception is tranquil and balanced.

-

In the fourth, perception is perfectly equanimous, clear, and unmoving.

Whatever qualities there were in the first jhāna … he discerned those phenomena one by one as they actually are present, known, and understood them. He remained unagitated, mindful, and clearly knowing.

MN111

This shows perception being purified within concentration itself, and then expanded through insight, seeing impermanence, cessation, and non-self even in these refined states.

Mental Formations: Perception

Intention directs attention, and with attention, the mind turns toward an object. That turning leads to contact. Contact gives rise to feeling, and from feeling, perception unfolds.

The elements of radiance, beauty, the dimension of infinite space, the dimension of infinite consciousness, and the dimension of nothingness are to be attained through the stilling of perception

SN14.11

Perception itself is the vehicle, not an obstacle, to higher realization. To develop Right Concentration, perception must be trained, purified, and refined, to open successively subtler dimensions of experience.

Purifying perception is vital, because perception shapes our experiences. It determines what we react to, and how karma is created. When perception is clouded, by habit, defilement, or unwise attention, we misinterpret reality. We see permanence in what’s passing, beauty in what’s not attractive, self in what’s not-self.

But through mindfulness and wise attention, perception becomes unobstructed. We start seeing things as they truly are, free from distortion. And in that clarity, craving softens and clinging fades. The mind begins to lean toward tranquility.

To understand this purification, we need to look closely at perception itself, how karma shapes it, and how perception can become a vehicle for liberation.

So What is Perception?

Perception is the function that recognizes and labels: A shape: “tree.” A sound: “music.” It assigns meaning. It tells us what things are. But perception doesn’t stand alone. It works in tandem with feeling. They’re separate aggregates, yet deeply linked. Feelings color perception. Perceptions give rise to new feelings.

Both are shaped by past karma. And like a goldsmith with raw metal, we can work with them, purifying what’s unwholesome, cultivating what’s wise.

There are two kinds of perception to be aware of:

-

Passive perception: like seeing a color or hearing a sound. It arises, and passes, on its own.

-

Intentional perception: when the mind chooses to investigate, to sustain, or to fabricate a view. This can be wholesome, or unwholesome.

Perception alone doesn’t create karma. Karma only arises when intention clings, when we act on a perception, or spin a story from it.

If we perceive beauty, and lust arises, or perceive threat, and fear grips us, then intention has made the perception karmically potent. Wrong views follow. And suffering begins.

But perception can also be a path to freedom. If we intend to perceive emptiness, to rest in the view of impermanence, not-self, or unattractiveness, then perception becomes medicine. Rooted in Right View, it purifies the mind-stream.

It’s essential to understand that the perception of impermanence, not-self, and others are not abstract. They are experiential. To perceive impermanence is to watch feelings and formations arise and pass. To witness the flow, bodily, mental, and verbal, and see things as they really are: “There is fading away.”

We don’t cling to whether things exist or not. We see: “There is passing.” “There is changing.” And in that seeing, dispassion follows, cessation arises, letting go becomes possible.

Unless we learn to let go, any perception that passes through an untrained mind will be distorted, hijacked by greed, colored by aversion, and clouded by delusion. That’s why concentration matters. That’s why a steady, collected mind, and the deep stillness of abiding in jhāna are essential.

By using these perceptions, our goal is not to uncover some metaphysical or philosophical reality. It’s not about finding ultimate truth in the physical world. It’s more profound than that. It’s about refining perception so it’s no longer shaped by craving.

It’s about abiding without resistance. Responding, not reacting, with wisdom. And understanding, deeply, that there is nothing to cling to. Nothing to possess. Nothing to become. From that seeing, suffering dissolves, not as a denial, but as liberation.

Fabricating Perceptions

Sometimes, it’s skillful to shape the way we perceive things. After all, many perceptions aren’t just passing thoughts; they’re deeply rooted. They’ve been ingrained through years of habit, cultural conditioning, and karmic influence.

Take, for instance, that natural pull of attraction we feel toward the opposite sex. Even when we see clearly, unwholesome thoughts can still sneak in.

That’s where the Tathāgata offers a skillful approach: to intentionally fabricate perceptions to counter their unwholesome allure. For example, fabricating the perception of the unattractive. Not because the object itself is inherently repulsive, but because the mind needs guidance. Because when lust clouds our vision, suffering isn’t far behind.

This is not deception. It is medicine for the wandering mind. A crafted perception, used not to distort truth, but to loosen the grip of craving.

Fabricated perceptions, when used mindfully and purposefully, can become tools for liberation. If they reduce greed, weaken hatred, clarify delusion, and are applied at the right stage of practice, then they are wholesome. They are medicine for the mind.

Whatever is useful for the abandoning of unwholesome states and the development of wholesome ones, that is to be cultivated.

AN2.19

Perception is Conditioned

Consider that perception is by nature constructed. Perception is not objective truth; rather, it's a conditioned mode of recognition that can be trained.

So, when we perceive something as beautiful or desirable, that's already a filtered, fabricated way of experiencing it. If we train ourselves to also perceive its unsatisfactory, impermanent, or disagreeable aspects, we are not being untruthful. Instead, we are skillfully balancing our perception in order to avoid clinging and suffering.

Those who perceive permanence in the impermanent, pleasure in suffering, self in the non-self, and purity in the impure are beings with wrong views, with scattered minds, and without understanding.

AN4.49

Perception: The Stilling of Perceptions

The processes of Abandoning the Hindrances and developing the Seven Factors of Enlightenment are not two separate undertakings, but aspects of the same dynamic purification of the mind. Both involve the transformation of how perception operates and how the mind relates to its own objects.

The hindrances arise when there is clinging to the Perception Aggregate, when perception becomes distorted by craving, aversion, or delusion. The seven factors of enlightenment emerge when this clinging is released, when perception becomes calm, clear, and free from clinging. Thus, the essence of the training lies not in suppressing perception, but in stilling it through wisdom, letting go of clinging, allowing perception to become transparent rather than obstructive.

Disciples, whatever kind of perception there is—past, future, or present, internal or external, gross or subtle, inferior or superior, far or near—all perception should be seen as it really is with correct wisdom thus: ‘This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.’

SN22.79

When perception is recognized not as "my" perception, but simply as "there is perception", the tendency to cling to it as “me” or “mine” weakens. The mind ceases to fabricate new hindrances because it no longer takes perception as a foundation for craving or aversion. In this way, abandoning the hindrances is the relinquishment of the mind’s clinging to its own perceptual fabrications.

Right effort is used to guide attention toward wholesome and skillful perceptions. We learn to recognize when there is clinging to perception, when it propagates unwholesome states, and gently redirect awareness toward perceptions grounded in investigation, energy, joy, tranquility, and concentration. This redirection is not a matter of replacing one perception with another through willpower, but of refining perception through knowing. When perception is seen as impermanent and dependently arisen, it naturally loses its binding power.

As perception settles, the mind no longer projects permanence, satisfaction, or selfhood onto experience. What remains is a lucid awareness that discerns phenomena as they truly are, transient, conditioned, and empty of self. In this stilling, perception continues to function, but it no longer binds the mind; it becomes a vehicle for wisdom rather than delusion.

From this refined state, the Seven Factors of Enlightenment naturally unfold. They are the wholesome tendencies that arise when the mind is free from the turbulence of craving. Investigation, energy, mindfulness, joy, tranquility, concentration, and equanimity are not “added” qualities, but the natural functioning of perception purified by wisdom. The cultivation of these factors is therefore the cultivation of perception free from distortion. As the mind releases its hold on the aggregates, including perception, the field of awareness becomes steady and luminous.

Perception: Using Antidotes

Just as impurities in gold can be neutralized using chemical treatments that dissolve unwanted substances while preserving the precious metal, we can also purify our own perceptions by using antidotes.

Since the mind fabricates good and bad perceptions of the world and all other dualities, we can retrain or reprogram the mind by neutralizing perceptions that result in greed, aversion, and delusion. It’s a kind of re-programming, untangling our attachment to these polarities by introducing balancing perceptions.

For example, just as acids are neutralized by alkaline, fire is cooled by water, heat tempered by ice, and darkness dispelled by light, so too, the Five Hindrances can be met with countering perceptions. These include recognizing the unattractive to temper the attractive, evoking energy to counteract dullness, and applying goodwill to dissolve ill-will. There are many such practices, taught by the Tathāgata, designed to balance and clear the mind.

As our mindfulness deepens, we begin to see that certain patterns arise repeatedly. For example, we may notice tightness or tension in the body. At first glance, it appears to be physical. But with sustained awareness, it becomes clear: this tension is not just physical, it is a manifestation of ill will, rooted in unpleasant feeling and aversive perception.

This is where purification begins.

When we recognize aversion in perception, when we see that tension is being shaped and sustained by a mind that resists or rejects, we can counter this with the perception of goodwill.

Instead of verbalizing goodwill, we apply it through intention and directed attention, using proto-thoughts and gently bringing awareness to the area affected by ill will or tension. The perception of goodwill is infused into that space. By holding the tension in awareness with goodwill, the perception is purified. The aversive construct begins to dissolve. In its place, a sense of brightness or joy may naturally arise.

Likewise, when there is dullness or heaviness in the mind, when perception is foggy or flat, it may be the result of sloth or torpor. We do not need to fight it directly. Instead, we can introduce the perception of energy, alertness, attentiveness, presence. Simply by attending to the experience with a slightly more upright, awake quality of perception, dullness can lift.

This is a subtle but powerful form of practice. We are not changing what arises: tension, dullness, irritation, but we are changing how it is held in perception. Each hindrance has a corresponding counter-perception that helps to disentangle the mind from its unwholesome shaping.

This process is moment-to-moment. With mindfulness, we observe the quality of perception, notice when it is influenced by a hindrance, and gently introduce the opposite quality. Over time, perception itself becomes clearer, more balanced, and less reactive. This is purification, not in theory, but in practice.

Perception: Fabricating Impermanence

The Tathāgata frequently spoke of the perception of impermanence as a key to liberation. Yet this perception itself is a fabrication, intentionally cultivated. It begins as a mental exercise and culminates in direct knowledge where fabrication ceases.

When the perception of impermanence is developed and cultivated, it eliminates all sensual lust, it eliminates lust for existence, it eliminates all ignorance, and it uproots the conceit ‘I am.’

AN7.46

The words “developed and cultivated” show that this perception is not innate but trained.

Perception as Conditioned

Feeling, perception, and consciousness are conjoined, not disjoined. What one feels, one perceives; what one perceives, one cognizes.

MN47

Since perception is dependently arisen, shaped by contact and attention, the perception of impermanence arises through right attention and reflection on the Dhamma. It is a wholesome fabrication.

In MN 62 the Tathāgata instructs his son Rāhula:

Develop the perception of impermanence, Rāhula, for when you develop the perception of impermanence, the conceit ‘I am’ will be abandoned.

MN62

This is a deliberate training of perception, a skillful use of fabrication to dismantle unwholesome fabrications. It is not deception, but a training of perception to accord with truth.

Fake It Until You Make It

At first, one may train the mind to see impermanence by intentionally creating the perception of impermanence, for example, seeing moving pixels where there appears to be solidity, seeing the wind or fire element where there is clinging, or even something as simple as melting ice cream, instead of solidity, if it helps the mind to see impermanence directly.

The breath, as a bodily fabrication, is one of the most effective ways to cultivate the perception of impermanence. Since the perception of breath itself is already fabricated, arising through feeling and perception, we can skillfully use it to breathe into any place where solidity is felt. By doing so, the mind learns to soften rigidity and recognize movement where it once sensed solidity. This practice not only develops the perception of impermanence but also reveals, through direct experience, that all phenomena are fabricated.

This “faking” of perception is not a lie, because actually we are restoring accuracy, since our ordinary perception of permanence is the true distortion. We are training the mind to see impermanence where it normally sees stillness. Gradually, this fabricated perception leads to direct seeing, and no effort is required.

First, one fabricates attention toward impermanence. Then, the insight becomes spontaneous, no longer constructed. Finally, even that perception ceases, as wisdom sees all formations as impermanent, including the perception itself.

Perception: Disrupting the Chain of Suffering at the Root

Purifying the mind means cutting off the chain of suffering at its root.

To understand this, we must turn to the Tathāgata’s teaching on dependent origination. In his teaching, suffering does not arise all at once, it unfolds as a process, an energetic momentum: from contact, to feeling, to craving, to clinging.