Abandoning the Hindrances

Whoever has gained release from the world, is gaining release, or will gain release, all of them have done so by abandoning the five hindrances, the mental impurities that weaken wisdom, and by firmly establishing their minds in the four abidings of mindfulness, and by developing the seven factors of enlightenment as they really are. This is how they have gained release from the world, are gaining release, or will gain release.

AN10.95

Abandoning the Hindrances: Introduction

The practice of Abandoning the Five Hindrances is the purification of the mind-stream from the mental impurities that obstruct wisdom. The hindrances are habitual tendencies that prevent sustaining Right Mindfulness, dwelling in the Four Dwellings of Mindfulness, and maintaining a collected and concentrated mind.

They obscure subtle states of mind, hinder entry into and abiding in jhāna, and ultimately block advancement on the path to liberation.

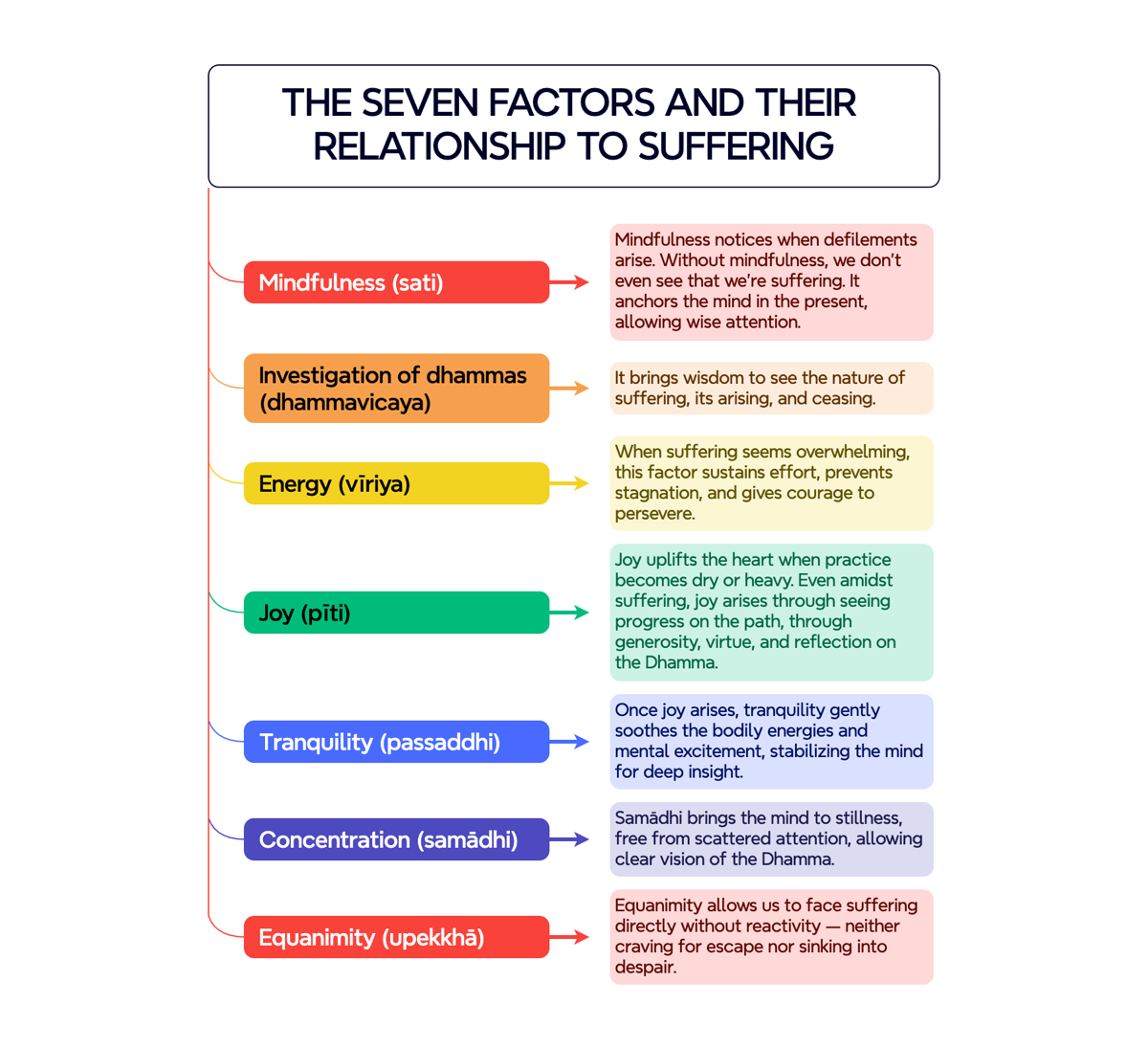

At this stage of the Gradual Training, the hindrances are abandoned through the cultivation of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. These factors balance and clarify the mind, enabling it to perceive and penetrate all phenomena with wisdom and equanimity. When fully developed, they lead to nibbāna, the complete knowing and ending of suffering.

The Aim of This Stage of the Practice

The aim of abandoning the hindrances and developing the seven factors is practical and direct: the cultivation of the “higher mind.” This is a pliable mind because it is no longer weighed down by distractions and fixations that arise from being bound to the physical domain. Freed from these constraints, the mind becomes flexible, responsive, and capable of subtle refinement.

Dwelling in this higher mind, the mind’s innate capacities become accessible. We can abide in different modes, such as joy, tranquility, or equanimity, through intention alone. This pliancy does not arise through fabrication but through the steady nourishment of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, which deprive the hindrances of the energy that keeps the mind brittle and reactive.

For this reason, this stage is essential for further development in the Gradual Training. The hindrances are not mere distractions; they are active distortions that bind the mind to tension, restlessness, and doubt, obscuring the clarity required for deeper knowing. The Seven Factors work directly against these distortions. As they mature, the hindrances lose their grip and fade, revealing a mind that is unified and ready for Right Concentration, the next stage of the Gradual Training.

It’s important to keep in mind that although the hindrances are temporarily abandoned at this stage, their deeper roots remain intact. What is being developed here is only the degree of purity required to consistently enter Right Concentration. Only when Right Concentration is established and mastered does the mind become subtle enough to directly see the taints and bring them to an end at their source.

The Purification of the Mind-Stream

As we practice Abandoning the Hindrances and developing the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, craving energy, instead of landing and taking form as a hindrance, is released, and the mind-stream becomes purified.

While the practice is simple in principle, its application requires consistent, moment-to-moment persistence.

As we practice dwelling Mind in Mind, we start to see the mechanics of how craving energy attempts to land and take hold, noticing how it leans toward an object, tightens around an idea, or begins to gather into a specific hindrance. As we fully see this movement and stop feeding it, the energy loses its power to become a hindrance.

Through this practice of seeing without feeding, craving energy loses its momentum. The agitation it once generated settles on its own, and a natural ease takes its place. We experience this relief not as something we created, but as the direct result of releasing strain in both body and mind.

As the tension of clinging dissolves, the energy that was previously bound up in the hindrances is liberated. From this freed energy, joy (pīti) arises naturally, not as a restless excitement, but as a quiet, steady gladness born of being unburdened.

By actively applying mindfulness, investigation, and energy, the mind naturally inclines toward balance. As we dwell Mind in Mind, the mind settles into a state of calm, steadiness, and clarity, allowing tranquility and concentration to mature through our practice.

This is how the energy that hindered the mind is reclaimed and stabilized. What previously fueled disturbance is purified through knowing and becomes the foundation for a contented, unified mind. Gathered and purified, the energy that once fed the hindrances is now ready to be directed toward their permanent ending.

Abandoning the Hindrances: Prerequisites

Reaching this stage of practice requires us to dwell Feelings in Feelings until the “sign of the mind” becomes clear. As clarity develops, our practice naturally inclines toward the source of experience itself: Dwelling Mind in Mind.

Although the Four Dwellings of Mindfulness are often taught as distinct categories, in our practice they function as a single, unified experience seen with increasing refinement. Each dwelling is not a separate practice but a more precise way of discerning what is already present. This is the development of increasingly subtle attention, allowing us to contemplate experience closer to its roots. We do not leave the earlier practices behind; we are still attending to bodily, verbal, and Mental Formations, but we are now contemplating them at their point of origin.

Body as the Ground

We maintain mindfulness of the body as our essential grounding. At this stage of the practice, instead of dwelling in the physical body, we start to dwell in the mental body. From this subtle dwelling, it becomes easier to observe how nāma constructs a representation of rupa, which is form, and how it habitually clings to it. Because nāma is the mind, dwelling Mind in Mind allows us to address this clinging directly at its source, seeing the "will-to-form" before it even crystallizes into physical tension.

Feelings as the Tone

Similarly, we remain sensitive to feeling-tone; this sensitivity does not take us away from the body, as we experience feelings arising through contact within the frame of the body. We are simply perceiving the same landscape with finer resolution, seeing how an entire world of personal identity is built from a simple pleasant, painful, or neutral tone.

As the feeling-tone becomes clearer, the inclinations behind it reveal themselves. Pleasantness brightens and "pulls" the mind, pain tightens and "pushes" it, and neutrality allows it to drift or steady. Detecting these subtle shifts in the mind’s "posture" is where we catch the energy of craving before it fully manifests. Recognizing this is the true beginning of Dwelling Mind in Mind.

The Mind as the Source

By Dwelling Mind in Mind, we address our bodily formations, feelings, and perceptions at their source. We have not moved to a different domain; we are simply seeing the “mechanics” behind the movements of form and feeling. From this vantage point, we don't just see the result of a hindrance; we see the quality of the mind as it begins to tilt toward greed or aversion. We feel the pressure of craving as a subtle inclination of the mind-stream, catching it before it gains the momentum of a full-blown hindrance.

Seeing Phenomena

As our practice matures, universal patterns and conditions become clear. This is dwelling in phenomena, the most transparent perspective within the Four Establishments of Mindfulness. We begin to discern the underlying conditions shaping intention, attention, contact, and perception.

Greed and aversion are no longer experienced as personal flaws, but as impersonal events arising and fading according to conditions. Energy and dullness, mindfulness and clarity, are recognized as natural movements of the mind—qualities that can be nourished or allowed to fade. The body is present, feelings are present, and the mind is known, but now the relationships linking them are directly seen.

It is important to keep in mind that this is not an absolute progression of the training. Depending on conditions and the strength of the hindrances present, it may be necessary to return to simply dwelling body as body or feelings as feelings.

In any case, this remains the direction of practice: to trace craving to its root, to see where this craving-force first lands in experience, and to use the clear light of the Seven Factors to discern the path leading to the end of suffering.

Abandoning the Hindrances: Right View

Before beginning the practice, it is essential that we first establish a clear foundation. Right View of several key principles is essential because they shape how our practice unfolds.

We need to know how to effectively redirect and purify craving energy, which is tainted by our past habits, and transform it into a purified mind-stream that can be used to destroy the taints.

These key principles include:

-

The Nature of the Hindrances as Craving Energy: Why it’s important for us to see the hindrances not as static descriptions but as craving energy seeking to establish itself and take root in our experience. We use the framework of Dependent Arising as our map to guide us in exactly where to look for this energy before it seeks to land and solidify.

-

The Manifestation of Energy: How this craving-force, when tainted by the subtle hindrances, manifests as a specific "flavor" or "pressure" in our immediate experience.

-

Abiding Mind in Mind: Why recognizing the Sign of the Mind and learning to abide Mind in Mind is the only vantage point high enough for us to see these subtle hindrances directly as they seek to land and solidify.

-

The Fabricated Mind-Stream: Understanding the nature of Mental Formations to see how our mind is being fabricated in real-time. By understanding this, we learn how to purify the flow of energy that has been shaped by our past habits.

-

Wise Attention: Why Wise Attention is the specific alchemical tool we use to redirect the mind's focus and release the grip of craving before it crystallizes.

-

The Mechanics of Clinging: Why Perception is the key aggregate we work with, the lens that determines whether the pressure of craving "lands" on our experience and sticks, or simply passes through.

-

The Nutriments of Craving: What the specific nutriments are that feed this craving energy, allowing us to starve the hindrances at their source.

-

The Alchemy of the Mind: How we systematically develop the Seven Factors of Enlightenment to transform hindered, heavy energy into the liberated, refined energy required for liberation.

The aim of this stage of practice is to abandon the hindrances and purify the mind-stream so that it naturally leads into the stability of Right Concentration, where the purified mind becomes malleable and bright and ready to destroy the taints.

Again, while an initial understanding of these concepts is important, there is no need for us to hold on to them tightly. A simple familiarity is enough at the start to ensure that when we encounter these states in practice, we recognize them not as "me," but as an impersonal, flowing process to be purified and released.

Let us now look at each of these key concepts in sequence.

Abandoning the Hindrances: The Five Hindrances

Let’s begin with a brief review of how the Five Hindrances are traditionally described:

-

Sensual Desire: This is craving to satisfy the senses, the desire for sensual gratification and clinging to pleasurable sensory experiences, sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and physical sensations. The mind becomes entangled in longing and attachment.

-

Ill-Will: This refers to aversion in its many forms, hostility, resentment, irritation, or anger—directed toward ourselves, others, situations, or states of being.

-

Sloth and Torpor: Sloth is a dullness or sluggishness of mind, while torpor is both physical and mental inertia, manifesting as drowsiness, heaviness, or a lack of energy.

-

Restlessness and Worry: This is a state of mental agitation, where the mind is unsettled by anxiety, regret, or unease. It involves being preoccupied with past or future events, which prevents inner stillness.

-

Doubt: This is the wavering of the mind—skepticism, indecision, or lack of confidence in the teachings, in the path, or in one’s own capacity to practice and awaken.

Despite their differences, all five hindrances share a common root: craving. In each case, the mind reacts to experience by craving pleasure, pushing away discomfort, or distracting itself from the present moment. This reactivity disrupts mindfulness and weakens concentration, obscuring the clarity needed for insight.

At this stage of the Gradual Training, the Five Hindrances no longer appear in their coarse forms. They show up instead as more subtle inclinations—residual currents of intention, reflexive movements of the mind, or preferences that lean experience in one direction or another.

Abandoning the Hindrances: The Gradual Training

As we advance through the stages of the Gradual Training, we address the hindrances in a systematic manner. At each stage, we cultivate specific skills to overcome the hindrances at their current level of manifestation.

-

The Practice of Sīla: We let go of desire, aversion, and attachment in our interactions by practicing Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood. We renounce expectations and assumptions, avoiding harmful interactions that disturb the mind while cultivating goodwill toward everyone.

-

Guarding the Sense Doors: We learn to avoid entanglement by not clinging to sensory signs or features that provoke greed, aversion, or delusion at the moment of contact.

-

Moderation in Eating: We practice restraint at the point of consumption, resisting the urge to delight in or crave flavors, ensuring the body is supported without the mind becoming burdened by indulgence.

-

The Practice of Wakefulness: We maintain a clear mind by guarding the sense-gates, ensuring we do not get lost in unwholesome thoughts triggered by external objects. At this stage, we address the hindrances as they manifest in these grosser thoughts through "external" corrective practices—such as the contemplation of body parts, the inevitability of death, and the sign of the unattractive—to neutralize the mind's initial "pull" toward the material realm.

-

Right Mindfulness: We establish ourselves in the Four Dwellings of Mindfulness, purposefully subduing greed and aversion for the "world."

At this more advanced stage of the Gradual Training, the Five Hindrances no longer appear in their coarse, narrative forms. Because the external "leaks" have been plugged through Sīla and Wakefulness, the mind’s sensitivity sharpens. We start to notice the hindrances not as "stories" or "thoughts," but as subtle currents in the mind’s stance toward experience.

All of these subtle hindrances share the same underlying quality: reactivity. The mind "leans" toward pleasantness, pulls away from discomfort, or drifts toward a false sense of safety. Each of these micro-movements disrupts the mind's pliancy and prevents the transition into Right Concentration.

By identifying these movements at their source, Dwelling Mind in Mind, we can apply the Seven Factors of Enlightenment to harmonize the mind-stream, shifting from a state of reactive "abandonment" to a state of mastered "stillness."

Abandoning the Hindrances: The Stages of Liberation

As we continue on the path to liberation, it's worth noting that the Five Hindrances can't be completely eliminated until we reach a stage of liberation. But with each step forward, we can weaken and overcome them enough to abide in jhāna.

As we advance through levels of liberation, some of the hindrances are permanently eliminated:

-

At the initial stage of liberation, Stream-entry, doubt is finally eliminated. We've got a clearer understanding of the path and our own abilities.

-

After the second stage of liberation, Once-returner, sensual desire, ill-will, and remorse are greatly weakened.

-

By the third stage, Non-returner, sensual desire, ill-will, and remorse are gone for good. These negative tendencies no longer hold us back.

-

And at Arahantship, the highest level of liberation, sloth and torpor, as well as restlessness, are completely eradicated.

Therefore, every step taken in weakening these hindrances brings us closer to liberation, where freedom from them becomes unshakable.

A person who has completely destroyed the taints, or mental intoxicants, sensual desire, existence, views, and ignorance, has developed and well-developed the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. This person is called an Arahant, a fully enlightened being.

Abandoning the Hindrances: Manifestations of Karmic Energy

As we begin the practice of abandoning the Five Hindrances, we need to see the subtle hindrances as manifestations of karmic energy.

Karma is essentially a form of mental energy. It possesses both momentum and volition, and it is deeply rooted in our past desires. These desires then manifest as intentions to fulfill those very desires.

This mental energy, which carries power behind it, is what drives our fundamental desire for existence itself. It is what creates the sense of "being," and importantly, the desire to take birth in a physical body, all to seek satisfaction out in the world. And this desire, in turn, manifests through our bodily, mental, and verbal actions, what the Tathāgata refers to as bodily, mental, and verbal formations.

Since karma is rooted in greed, aversion, and delusion, it shows up in the present moment as a restless, scattered mental energy. It is constantly seeking satisfaction, always seeking to "feed" on the objects of the world, which is what we call craving for sense satisfaction. This continual seeking and the underlying restlessness it causes result in a mind that is tainted and disturbed, clouded by ignorance, and ultimately, incapable of achieving liberation.

The Goal is Not Purification of Karma

The aim of developing the Seven Factors is not to purify karma, since past causes and conditions cannot be altered. The aim is to know karma completely, to see it as not-self, and to no longer become entangled in it. In this way, new karma is not created, the cycle of rebirth is brought to an end, and future suffering ceases.

As we move through the Gradual Training and develop the Eightfold Path, scattered mental energy begins to subside. The mind becomes more collected and settled, increasingly unified around the aim of liberation.

Yet even at this stage, restlessness still lingers. There remains a current of ingrained karmic momentum, continually seeking expression through the desire for existence, clinging to the Five Aggregates. This underlying agitation keeps the mind from fully coming to rest.

It is this unsettled condition that the discourses describe as the “five impurities of the mind.” When these are present, the mind is neither pliable, nor workable, nor radiant. Lacking these qualities, it cannot properly attain the concentration required for the destruction of the taints.

For this reason, genuine movement toward liberation depends on transforming this impure and scattered mental energy through the cultivation of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. As these factors mature, the mind is refined into a steady stream of pliant, collected energy, unified and directed toward the ending of the taints.

Abandoning the Hindrances: Craving and Dependent Arising

When trying to understand craving, we need to see craving not as suddenly appearing after feeling, but as an energy inherent in the whole chain of dependent arising.

Craving is not a momentary occurrence; it is a current of karmic energy searching for a foothold. When it lands, it shapes the entire chain of dependent arising and our entire experience.

Ignorance

Ignorance gives craving a place to hide. When anything in experience is taken to be substantial, lasting, dependable, or satisfying, and when experience is framed as me, myself, or mine, craving finds its footing.

Because these views are assumed rather than examined, conditions are no longer seen clearly. We cannot distinguish between the simple arising of experience and the pull of craving. Drawn by that pull, we become lost in the very views we have constructed, unable to see that these same views are the cause of our suffering.

Volitional Formations

Volitional activity, which is past karma shaped by the pull of current experience, forms intentions around already existing inclinations and tendencies. These intentions already contain the energy of craving from past karmic volition, which is now searching for a foothold, trying to obtain satisfaction in existence.

This craving and the resulting intentions set the stage for action by shaping which possibilities we choose and which we avoid. This is craving taking shape before it is recognized as craving.

Consciousness

As consciousness meets experience, it continually seeks a foothold—the craving to establish the sense of “I am here.” It does not create a self from nothing; rather, driven by this craving energy and its preferences, it repeatedly re-establishes a position within the body and the “world.”

Name and Form

Name continually reshapes what comes through the six senses into mental images, forming a representation of a “world” and its objects. Sensations, perceptions, intentions, and the surrounding environment are organized into a coherent field of experience that supports the sense of being.

Depending on what arises, this field expands or contracts: a pain in the knee, for example, pulls attention inward and centers awareness around that sensation. Consciousness and name and form work together in this ongoing positioning, creating a lived world that feels immediate and personal, even before clinging solidifies a sense of self.

The Six Sense Bases and Craving

When the sense bases are active, craving is continually responding to conditions, searching for something to land on. With contact, feeling arises—pleasant, painful, or neutral—depending on the presence of craving. Here craving becomes more visible: the pleasant offers a way to continue becoming, the painful offers something to escape from, and the neutral offers something to ignore.

Yet even before we react, craving is already leaning. It tries to shape the next intention, the next interpretation, and the next idea of who we are in relation to what is happening. In other words, craving drives the experience.

Clinging

As the chain unfolds, this current of energy seeks to solidify itself. It looks for a form to inhabit and tries to gather a sense of identity from whatever it contacts. It wants a place to stand, a role to assume, and something to protect or enhance.

This movement carries on into clinging, where the mind tightens around a particular view, feeling, memory, or sense of self. That tightening is craving attempting to secure a foothold, to make its position feel stable and real.

Becoming

From there, becoming follows naturally. The volitional momentum has built enough force that the mind constructs a whole state of being around it. This may be a mood, a posture, a reactive identity, or a storyline that tries to complete itself.

Eventually birth takes shape, meaning the appearance of a fully formed state that feels personal. Aging and death represent the fading of that constructed state, followed by another cycle as craving searches for a new foothold.

Experience Itself is the Result of Craving

The key point is that craving is not just a reaction to feeling; everything in our experience can be seen as the result of craving. Experience itself is craving trying to become. Our practice is not to force this movement to stop but to understand how craving continually seeks to anchor itself in our experience, in each link of dependent arising.

When this is seen clearly over and over again, its momentum naturally weakens. It no longer finds the solid landing places it depends on. The chain still operates, but the inner drive that renews suffering begins to fade.

So to practice correctly, we need to see our experience as the direct expression of dependent arising and craving energy. Nothing is hidden; it is all right here for us to see.

Using our own experience as the laboratory, we learn to discern how craving moves through each moment, how it sustains bodily, mental, and verbal formations, and how it can gradually be released.

When we use Dependent Arising as a framework to guide our practice, we not only penetrate the core teachings more easily, but we also direct our efforts toward the heart of the problem itself.

Abandoning the Hindrances: The Manifestation of Craving Energy

Now that we have covered how craving energy tries to land in our experience based on Dependent Arising, let's turn our attention to how it manifests.

The energy of craving is persistent; when it no longer has “the world” to land on, it turns inward and latches onto the only thing left: the Five Aggregates. At this stage, the hindrances are no longer about external objects. They are craving energy, landing on the internal processes of the mind, on the very foundations of experience, on the intentions, attentions, perceptions, and feelings that we are observing.

Whether it is subtle greed for a pleasant feeling or subtle resistance to a neutral one, the hindrances form when the craving-force latches onto these internal flows. Let's look at some examples of how these subtle hindrances manifest.

Sensual Desire: The Demand for Satisfactory Experience

Even when gross craving has subsided, sensuality persists as a subtle desire for the internal landscape to be “just right.” It is the craving for experience itself to be satisfactory. This is nāma seeking to cling to its own activity, where craving energy manifests as a preference for certain pleasant internal feeling tones, such as ease in the breath or soft vibrations in the body.

We might catch the mind trying to solidify perception by prolonging a moment of peace, brightness, or spaciousness, attempting to “freeze” a favorable perception. This is often accompanied by a lusting for attention, where we treat a particular mode of attention as a possession because it feels smoother or more agreeable. Underneath it all is an expectation, a wish for our practice to unfold in a familiar or satisfying way, treating the aggregates as a “nest” for the self.

Ill-Will: Experiential Intolerance

In our practice, ill-will no longer appears as anger. It becomes a subtle resistance to the way phenomena present themselves, a craving to get rid of irritation and tension. We feel this as a "push", a tightening or shove in intention when a neutral or unpleasant sensation arises in the Form Aggregate.

There is often a background reluctance to tension, where we find ourselves treating a physical sensation as an error in the system rather than an impersonal event. This manifests as a shrinking away from dullness, heaviness, or mental fog, or as a subtle aggression toward the present moment because our perception does not match how we think the practice “should” be progressing.

Sloth and Torpor: Landing on the Neutral

These are not gross lethargy but nāma clinging to the comfort of the dim. Here, the pressure of craving lands on the Consciousness Aggregate to find safety in non-doing. We notice a sinking or a softening of alertness when the mind encounters something neutral, using that neutrality as a place to hide.

This shows up as a subtle preference for a pleasant haze or blurry perception rather than the sharp friction of clear, balanced attention. It is a withdrawal of effort that weakens our investigation, letting intention slump into an unproductive ease.

Restlessness: The Momentum of Becoming

Restlessness is a craving-force spinning within our volitional formations, unable to let the momentum of doing settle. We feel it as a continual "reaching" of the mind toward the next moment, where attention cannot stay with the current point of contact.

This creates an anticipatory energy; even when attention stabilizes, the mind is waiting for a result to happen. We might feel a background "hum" of unease, a subtle vibration of the “I” trying to manage our experience through constant, unnecessary readjustments of attention.

Doubt: The Clinging to Certainty

Doubt no longer appears as explicit questioning. It becomes craving energy landing on the whole process with a sense of insecurity. It manifests as a hesitation or a reluctance to abandon unskillful patterns because the groundless nature of nāma, unbound from rūpa, feels unsafe. We find ourselves mistrusting or second-guessing the quality of our own attention, looking for a conceptual guarantee rather than trusting our direct vision. There is often a tension over the outcome, where we watch the result of our practice with a managerial eye, as if checking whether the investment of practice is paying off.

While these are only a few examples of the subtler hindrances, understanding them as craving landing on the aggregates allows us to recognize them as impersonal patterns.

When we see the landing as it happens, through the immediate change in the sign of the mind, we can use the Seven Factors to release the grip, revealing a mind that is pliant, unified, and truly dwelling Mind in Mind.

Abandoning the Hindrances: Dwelling Mind in Mind

Now let’s turn our attention to how we work with craving and the hindrances by dwelling Mind in Mind.

At this point in the Gradual Training, we are not expected to dwell Mind in Mind in a complete or continuous way. The hindrances are still present, even if weakened. We are cultivating and have not yet perfected the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. What we are developing is the conditions for reliably dwelling Mind in Mind and staying in Right Concentration. This stage is about development, not mastery.

When we dwell Feelings in Feelings, something subtle begins to open. Feeling is no longer immediately taken up as something to pursue, resist, or ignore. In that clarity, the “sign of the mind” can be recognized. We begin to sense the quality, tone, and movement of the mind itself as it responds. What becomes visible is not a reactive mechanism but a living current shaped by the energy of craving.

The Mind has no Location

When trying to dwell Mind in Mind, it's important to understand that because the mind has no location in space, it cannot be found at any physical point or within any container. Anything that we experience in the physical domain is not the mind. To dwell Mind in Mind is therefore not to escape the body but to stop taking physical form, rūpa, as the basis for experience. It is to remain within nāma, the domain where experience is actually being shaped.

What we call “mind” is a living stream in which intention, attention, feeling, perception, and contact arise according to conditions. This stream is already charged by past habits of wanting and resisting. It leans and searches for a place to land. If it lands on the physical, it appropriates the body or another physical object, and we are no longer dwelling Mind in Mind.

Knowing the Mind

To dwell Mind in Mind is to meet this current before appropriation and propagation occur. Just as with feelings, we aim to remain with the mental movements of intention, attention, contact, feeling, and perception without letting them become “my body” or “my feelings.” In ordinary experience, these components immediately solidify into ownership and story. This is where the mind is swept away by its own fabrications.

When we dwell Mind in Mind:

-

Intention is felt as leaning energy before it becomes “I want.”

-

Attention is seen as the mind’s turning toward before it becomes “I am focused.”

-

Contact, feeling, and perception are known as the charged movements of the mind before they become “this is happening to me.”

By staying here, our attention does not rush outward into appropriation and propagation. The chain that normally crystallizes into bodily, mental, and verbal formations is seen in its earliest stirrings. The mind remains with its own movement. We stay with the current itself, seeing the “Sign of the Mind,” its urgency, its softness, its contraction, and its release, as it actually happens.

In this dwelling, appropriation and propagation find no footing. What ceases is creating stories. Feeling is just feeling. Perception is just perception. Mind is simply mind. Without appropriation and propagation, suffering has no place to take hold.

This is the doorway to Right Concentration, unification within the mind’s own domain.

Purifying the Mind: The Sign of the Mind

To abandon the hindrances and develop the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, the mind must first learn how to recognize its own state. This recognition is what the teachings call the "Sign of the Mind." Without this sensitivity, practice remains indirect; we stay unsure whether a subtle hindrance is lurking, whether it has truly faded, or if a factor is developing appropriately.

As agitation, dullness, desire, resistance, and doubt weaken, the mind begins to stand out from its objects. Experience no longer "lands" on external sights or sounds; instead, attention remains within the mental sphere. At this point, the mind becomes visible to itself—not as a physical thing, but as a quality. This is where the Sign of the Mind appears.

What is the Sign of the Mind

The Sign of the Mind is not a shape or a visual image. It is the distinctive pattern, texture, or tone of consciousness that becomes apparent once grosser distractions subside. It is the felt quality of the mind’s own activity—more precisely, it is volitional formation in action. When the mind intends, attention is shaped by past karma, and that "shaping" is the mark by which the state of the mind is known.

Because the mind has no physical location, it cannot be known as an object. Instead, it is known through its activity. When the mind is clear, its activity is luminous; when gathered, it is steady. When a hindrance is present, it appears immediately as a change in the tone, weight, or movement of attention itself. In this context, "sign" means the mark by which something is recognized. Even the earliest stirrings of craving can be detected as a subtle alteration in the sign, provided the mind is sufficiently secluded from sensory pull.

How is the Sign of the Mind Recognized

The ability to recognize the Sign of the Mind is the natural outcome of "dwelling feelings in feelings." As attention stops moving outward toward the senses, the clouding effects of the hindrances thin out.

With mindfulness of the body, bodily formations settle. With mindfulness of feeling, pleasant, painful, and neutral tones are known clearly without reaction. As reactivity diminishes, experience is no longer dominated by the "collision" of sensory contact. Attention shifts away from heavy, localized sensation toward the subtler movements of mind.

When the signs of body and feeling have quieted, the Sign of the Mind is uncovered. It appears simply as mind, known through its quality, as described in MN 10:

One knows the mind with craving as a mind with craving, the mind without craving as a mind without craving, the mind with aversion as a mind with aversion, the mind without aversion as a mind without aversion, the mind that is collected, the mind that is scattered, the mind that is exalted, the mind that is surpassed, the mind that is unsurpassed.

MN 10

The Sign emerges not because something new has been created, but because the noise of the senses is no longer loud enough to obscure it.

Hindrances Appear as Changes in the Sign

Before hindrances manifest as full-blown thoughts, they appear as shifts in the Sign of the Mind.

-

Agitation fragments and unsettles the texture of attention.

-

Desire draws attention outward, creating a "leaning" toward contact.

-

Dullness flattens and dims the mental field.

-

Resistance hardens attention with a sense of pressure.

-

Doubt destabilizes the sign, making it hesitant and murky.

By the time narratives arise, the sign has already changed. When you learn to recognize these early alterations, hindrances lose their concealment. They are abandoned not by arguing with their content, but by clearly knowing the altered quality of mind and no longer sustaining the underlying intention. Recognition itself weakens the tendency to continue.

Intention, Attention, and Perception

The Sign of the Mind is known through the functional movements of intention, attention, and perception. Intention is the subtle leaning that sets direction; attention gathers experience and holds it; perception labels and colors what is known.

Together, these shape the "texture" of consciousness. When intention leans toward acquiring or resisting, attention becomes tight and localized, and perception narrows. When intention is settled, attention steadies and perception clears. In this way, the Sign is seen as a dynamic process of conditioned activity rather than a static "self."

The Sign in Direct Practice

In direct experience, the Sign of the Mind is the quality of attention itself. You can find it by observing:

-

The Tone: Is attention brittle or soft? Tight or spacious?

-

The Location: If attention feels "fixed" in the head, this often reflects a localized volition or clinging to a physical anchor.

-

The Luminosity: Is awareness bright or dim?

-

Reflexivity: Are you absorbed in the content of a thought, or can you feel the quality of the attention giving rise to that thought?

Practice means resting with the intention and quality of attention. This is "knowing the mind" rather than being a "knower" located in the body.

Using the Sign to Abandon Hindrances and Develop the Factors

By attending to the Sign of the Mind, dependent arising is seen directly. The moment intention leans toward or away, the quality of attention shifts. This is craving known at its root, before it becomes emotion or story.

This sensitivity also guides the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. When the sign is dull, investigation and energy are required; when the sign is unsettled, tranquility and collectedness are needed to restore balance. Mindfulness is the continuous, clear-eyed knowing of the sign itself.

Finally, seeing the Sign of the Mind as a conditioned formation prevents the creation of a "refined observer." Even the clearest states are known as shaped and impermanent. There is knowing without ownership. When the Sign of the Mind is known in this way, the process of the mind is laid bare, allowing hindrances to fall away and the factors of enlightenment to mature.

Purifying the Mind: Understanding Mental Formations

To clearly recognize the Sign of the Mind, dwell Mind in Mind, and purify the mind-stream of the hindrances, we must first understand what this mind-stream actually is.

It is not a fixed entity flowing through time, nor a hidden self behind experience. The mind-stream is the ongoing flow of conditioned mental processes arising and passing moment by moment. It is the dynamic unfolding of contact, feeling, perception, intention, attention, and consciousness, all dependent on causes and conditions and shaped by past karma. Purification does not mean replacing this stream with something else; it means knowing it so clearly that ignorance no longer shapes it.

Dwelling Mind in Mind means knowing these processes rather than being lost in their contents. Instead of being absorbed in thoughts, emotions, identities, or narratives, we learn to recognize how the mind is operating.

What are Mental Formations?

Understanding Mental Formations is central to this purification. Mental Formations are the hidden architects behind every experience we have. They are not limited to obvious intentions or deliberate choices but include the deeper volitional currents of the mind rooted in intention. They are the way intention unfolds into lived experience.

Mental Formations are shaped by karma, with intention as their core. Karmic intention is the initial leaning of the mind, the choice to resist, pursue, or release. Mental Formations are how this intention propagates into our lived experience, unfolding in dependence on present causes and conditions.

For example, when an unpleasant sound is heard and an unpleasant feeling arises, karmic intention appears as the impulse to react or resist. Mental Formations then carry that impulse forward, tightening our attention, labeling the sound as “disturbing,” and generating habitual patterns of commentary and response. In this way, intention sets the direction, and Mental Formations elaborate and sustain that direction, organizing our experience moment by moment within dependent arising.

These formations include tendencies to aim, resist, pursue, hold, or release. They are not passive events. They actively structure our experience by directing attention, shaping perception, and organizing responses. In this way, they give continuity and momentum to the mind-stream and quietly condition consciousness, action, and future experience.

What is Clear Knowing?

Clear knowing is our direct recognition of contact, feeling, perception, intention, attention, and consciousness as they arise. Whatever goes beyond this immediate knowing is proliferation. The teachings emphasize staying with these processes because they reveal fabrication at its source. This is what it means for us to dwell “Mind in Mind.”

Intention shows where the mind is leaning. Attention reveals what is being sustained. Feeling reveals the tone of pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. Perception shows how experience is marked and recognized. Consciousness is the knowing of an object itself. Dwelling Mind in Mind means remaining with this knowing without adding narrative, justification, or identity.

When we stay with bare knowing of contact, feeling, perception, and intention, experience is known before it solidifies into fabrication. This direct, non-elaborated presence is what is meant by knowing.

Simply understanding Mental Formations is not enough. We must know them directly, see how they arise, recognize the views that condition them, and understand their true nature as impermanent, conditioned, and not-self. When this is seen clearly, again and again, the craving-force loses its grip and the momentum of saṁsāra begins to loosen.

Purifying the Mind: The Process of Purifying Gold

The discourses compare the abandoning of the Five Hindrances to the process of purifying gold. Just as a goldsmith removes impurities, like iron, copper, tin, and lead, from raw gold through repeated smelting and refining, so too does a disciple remove sensual desire, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and remorse, and doubt through diligent practice.

As the impurities vanish, the mind becomes bright, malleable, and ready for work, just as purified gold is fit for crafting exquisite ornaments. In this purified state, the mind can penetrate higher wisdom for the destruction of the taints.

Disciples, these five impurities of gold, which, when present in gold, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly come to fulfillment in any craftsmanship. What are the five?

Iron, copper, tin, lead, and silver: these are the five impurities of gold, which, when present in gold, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly come to fulfillment in any craftsmanship.

But when gold is freed from these five impurities, it becomes pliable, workable, and radiant; it is not brittle and properly comes to fulfillment in any craftsmanship. Whatever ornament one wishes to make from it—whether a ring, earrings, a necklace, or a golden chain—it serves that purpose.

Similarly, these are the five impurities of the mind, which, when present in the mind, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly attain concentration for the destruction of the taints. What are the five?

Sensual desire, Ill-will, Sloth and Torpor, Restlessness and Worry, and Doubt: these are the five impurities of the mind, which, when present in the mind, make it neither pliable, workable, nor radiant, and it does not properly attain concentration for the destruction of the taints.

But when the mind is freed from these five impurities, it becomes pliable, workable, and radiant; it is not brittle and properly attains concentration for the destruction of the taints.

AN5.23

Just as a goldsmith carefully applies intention, attention, and effort to remove impurities, making gold pliable and ready to be shaped, we likewise cultivate Right View, Right Intention, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Investigation. Through this ongoing refinement, the mind and its perceptions are purified, clarity deepens, and the conditions for the ending of the taints are gradually established.

Mental Formations: Shaped by Views

To understand Mental Formations and how the mind-stream can be purified of the hindrances, we have to look beneath their surface expressions. At the root of Mental Formations lies something more subtle and more powerful: view. Not view as abstract belief, but as the deeply embedded assumptions that silently frame how reality is perceived.

The mind interprets experience through these lenses: I exist, this is mine, I am this body, I am the experiencer, I must be happy, I must be free from pain. These are not harmless ideas. They are underlying views rooted in ignorance, and from them craving, aversion, restlessness, sloth, and doubt naturally arise. These hindrances then shape how experience is felt, interpreted, and responded to.

Because ignorance conditions dependent arising, and Right View directly counters ignorance by undoing these assumptions, the cycle is undermined at its root. When wrong views loosen, dependent arising no longer takes hold in its usual way. Experience still unfolds, but it is no longer organized around distortion and clinging.

Letting go of wrong views begins with seeing how they structure suffering. Take the view “I am this body.” As long as this view operates, physical discomfort becomes personal suffering. Every ache, illness, or sign of aging feels threatening because it appears to happen to me. The body is no longer known as a changing, impersonal process, but as a fragile possession. From this, clinging arises, to comfort, youth, and control, and the mind becomes bound to the body.

From these views, Mental Formations follow. The mind begins to seek, control, preserve, fear, or avoid in order to protect the assumed self. These reactions feel natural, even necessary, yet they are conditioned constructions, karmic momentum set in motion by misperception. It is the view that activates these formations. When the view is seen through, the formations lose their foundation.

The difficulty is that the most powerful views often remain unseen. They do not announce themselves as beliefs. They function as assumptions taken for granted, quietly organizing perception and response. When they go unexamined, Mental Formations continue to operate beneath awareness, steering intention and shaping karma.

Freedom begins when this hidden machinery is brought into the light. By questioning what has never been questioned, and by no longer mistaking views for reality, the mind-stream begins to purify itself at its source.

Mental Formations: The Power of Intention

Purifying the mind-stream and understanding Mental Formations requires us to understand the power of intention itself.

When intention is clearly known, its force becomes unmistakable. The moment an intention arises, the movement of experience is already set in motion. Nothing needs to be pushed or managed. Whatever the mind intends immediately begins to take shape, and experience unfolds in that direction according to its own momentum.

When intention is unwholesome, shaped by the hindrances, it gives rise to stress and becoming. When intention is wholesome, it gives rise to ease and release. This is the power of intention. It does not merely influence experience; it actively constructs the worlds we inhabit, moment by moment.

This power becomes obscured when self-making overlays intention. As soon as the movement is claimed as “mine,” or a particular outcome is sought, doubt enters. The hindrances stir, craving colors the intention, and its direction weakens. Instead of allowing intention to unfold naturally, the mind adds effort, strategies, stories, and imagined control.

These added constructions do not strengthen intention; they compete with it. Conflicting motives arise, clarity is diluted, and what would have unfolded simply becomes entangled in fear, habit, and identity. The mind’s creative capacity remains, but it is buried beneath layers of confusion.

How Wrong Views Weaken Intention

Intention is also weakened by our limiting views. When the mind assumes it is bound to the body or confined to a narrow sense of possibility, it no longer recognizes its own freedom. Intention begins to feel like a wish rather than a force.

This happens because we have not yet seen what the mind is capable of. We have not discovered that joy can be formed, calm can be shaped, and entire modes of experience can be created through intention. Ignorance here is not a lack of intelligence but our unfamiliarity with the mind’s own potential.

Without confidence in this capacity, intention hesitates. We doubt its own reach. Qualities we have not yet tasted cannot be clearly envisioned, and so we do not intentionally cultivate them, or we approach them with uncertainty.

Revealing the Mind’s Natural Creativity

As our practice weakens the hindrances and steadies attention, something becomes clear. Intention does not require force or control. When self-making drops away and our limiting views loosen, intention reveals itself as a natural creative movement of the mind.

We begin to see that simply directing the mind shapes our experience. Ease, joy, brightness, and clarity can be intentionally formed. What may feel miraculous is simply recognition. The creative capacity was never missing, only obscured by doubt and the pressure of craving.

We develop intention, not to build a “self” or to get entangled in the “world,” but in the service of developing dispassion, cessation, and relinquishment.

The practice is simple, though it requires a purified mind. Whatever we genuinely intend unfolds naturally when it is no longer obstructed by self-making and conflicting motives. When the mind stops interfering, intention flows directly into Right Effort. This is Right Intention.

Mental Formations: Intention as the Shaping Force of Experience

To purify and develop the power of intention, we first need to understand the different ways that intention can manifest itself as a shaping force in our experience.

Intention is not simply the act of deciding to do something. It is the underlying pressure that shapes attention, feeling, perception, and response. It is the directional quality that turns raw contact into something oriented, something that leans toward, reacts against, holds onto, or avoids.

But with the remainderless fading away and cessation of ignorance comes the cessation of volitional formations; with the cessation of volitional formations, the cessation of consciousness... This is the cessation of this whole mass of suffering.

SN12.61

In Dependent Arising, volitional formations are not occasional choices; they are the continuous activity of intention operating whenever ignorance is present.

At its most obvious level, intention appears as deliberate action. For example, wanting to speak, choosing to move, and deciding to think something through. This level is easy to recognize because it is explicit and effortful. There is a clear sense of doing. But this is only the coarsest level of intention.

More subtle is intention as reaction. Before any deliberate choice, there is already a leaning. Pleasant experience draws the mind toward it, unpleasant experience pushes it away, and neutral experience is overlooked or ignored. This occurs automatically. The mind does not decide to want or resist; the wanting and resisting are already the intention. This reactive level often goes unnoticed because it feels natural, as though it belongs to the object itself rather than to the mind’s orientation toward it.

Subtler still is intention as management. This is the impulse to adjust experience so that it aligns with an underlying assumption. For example, trying to stay calm, trying to remain detached, trying to be mindful, and trying not to react. Even restraint can be intentional in this sense. The mind positions itself in relation to what is happening, maintaining a stance. This stance may feel refined or virtuous, but it is still a formation because it depends on a view that something needs to be handled.

At a very subtle level, intention appears as monitoring. There may be no obvious doing, yet there is a background sense of watching, checking, or keeping track. Is this still okay? Is this fading? Is this a distraction? Am I present? This monitoring creates a reference point, a center from which experience is being evaluated. That reference point is intention operating quietly.

Even more subtle is intention as assumption. Here, intention does not feel like doing anything at all. There is simply an unquestioned sense that what is happening is happening to someone, that it has a past and a future, and that it matters in a personal way. For example, a thought arises, and without any deliberate choice, it is already taken as my thought, something that continues, something that might lead somewhere good or bad.

Because it is silently assumed to be mine and meaningful, the mind automatically follows it, corrects it, worries about it, or tries to bring it to a better conclusion. No decision was made to engage; the engagement was already built into the assumption.

In this way, intention is already operating before any felt movement appears. When we take experience as personal, lasting, or significant, this creates a situation that seems to require a response. The protecting, extending, or fixing happens on its own, not because one chose to intend, but because the assumptions made intention unavoidable.

At this level, intention and ignorance are inseparable. Self-making, permanent-making, and satisfactory-making are not added on after experience arises. They are the way experience is framed from the start. As long as this framing is present, intention must operate. There is always something to do, even if that something is to remain still.

What is often mistaken for non-intention is simply intention that has become quiet, refined, or indirect. Silence, neutrality, spacing out, or absorption can temporarily suspend coarse intention, but the underlying structure remains intact. When conditions shift, intention resumes because the assumptions that require it were never absent.

The Cessation of Intention

Cessation of volitional formations, as described in Dependent Arising, is not the refinement of intention but its non-arising. This occurs when ignorance is absent, meaning self-making, permanence-making, and satisfactory-making are not operating. When nothing is being taken as self, as enduring, or as a source of fulfillment, there is no basis for volition. No leaning is possible because there is nothing to lean toward or away from.

In other words, when experience is not taken as self, not appropriated, and not measured against satisfaction or dissatisfaction, there is nothing left that would require intention to appear.

Without self-making, there is no one to act for. Without clinging, there is nothing to hold, resist, or resolve. Without satisfactory-making, there is no project to complete or secure.

Self-making, permanent-making, and satisfactory-making are not three independent processes that can freely operate on their own. They are three aspects of the same misreading of experience. Taking experience as "me" or "mine."

Experience may still occur, but it is not organized around a center, a timeline, or a project. There is no participation because there is nothing that requires participation.

Understanding intention in this layered way matters because the path is not about suppressing action or cultivating passivity. It is about seeing the assumptions of ownership that make intention seem necessary in the first place.

When experience is taken as me or mine, intention must arise to protect it, extend it, or make it work. As those assumptions weaken, intention loses its footing on its own. What ceases is not activity itself, but the compulsive shaping of experience driven by ignorance, specifically the taking of experience as personal, enduring, and capable of providing satisfaction.

This is why wisdom is recognized not by what appears, but by what no longer arises. When ownership is no longer assumed, the pressures that once automatically arose do not appear.

Mental Formations: Attention

Now we turn to the next component of the mind-stream: Attention. Because the quality of our attention determines whether we recognize the "Sign of the Mind" or fall back into the grip of a hindrance, we must know this faculty completely.

The Channel for Craving Energy

Attention follows Intention. When Intention sets the direction, Attention is the movement that follows. It is the channel through which craving energy flows into experience. When the mind intends to maintain a particular mood, such as irritation or desire, Attention immediately moves to "feed" that state by fixating on relevant objects. Even when attention seems resting, it is often being held in place by an underlying intention to remain "landed" on a specific aggregate.

The Precursor to Clinging

Attention comes before Perception; without it, Perception cannot arise. It is the silent cue that says, “Look here.” This is crucial because clinging starts with where we look. If Attention is captured by the "attractive" or "irritating" aspects of an object, Perception will inevitably follow with a distorted label, and a hindrance will crystallize.

The Mechanism of Growth

Attention is not passive; it actively shapes the mind-stream. Whatever we give attention to grows. In the context of the hindrances, unwholesome attention acts as a "magnifying glass" for craving. If we attend to the attractive aspect of an object, Sense Desire increases. If we attend to the "slump" of the body, Sloth and Torpor increase.

Purification through Wise Attention

The mind is purified not by "stopping" attention but by changing its quality. Unwise Attention is the act of the mind clinging to the surface narratives of the hindrances, which cements views and builds bondage.

Wise Attention, however, is guided by Right View. It directs the mind to see the process of the hindrance rather than its content. By ceasing to nurture unwholesome perceptions and instead directing attention toward the "Sign of the Mind," the craving energy has nowhere to land. The mind begins to clarify, brighten, and unify, transforming the "conduit of craving" into the "conduit of release."

To understand attention more deeply, let’s now look at how attention manifests and how it can be worked with.

Attention: From Ordinary to Supra-mundane

Attention is not neutral. It is an active movement of mind that shapes experience. When attention settles on an object, it does more than register it; it organizes experience around that object. From this organization arise further formations such as inner speech, evaluation, and meaning-making. Even when attention appears calm, it is still shaping what is known.

This matters because wherever attention is active, fabrication is active. Practice does not eliminate fabrication all at once. What changes is how attention functions. The way attention is applied determines whether it fuels agitation, supports restraint, or moves toward the fading of conditions.

This can be seen clearly by looking at attention in three types of persons: the ordinary person, the practitioner, and the Noble Disciple.

The Ordinary Person: Attention as Self-Chatter

For the ordinary person, attention is driven by habit and clinging. It moves toward what is pleasant, away from what is unpleasant, and drifts through what is neutral. Because experience is taken as me or mine, attention immediately triggers verbal fabrication in the form of commentary, stories, and judgments.

When attention lands on a sight, sound, memory, or feeling, it almost always gives rise to inner speech. “I like this.” “That was a mistake.” “What happens next?” This self-chatter follows attention automatically and reinforces identity and continuity. Each moment of attention becomes a starting point for proliferation, sustaining the sense of a self moving through experience.

The Practitioner: Attention as Skillful Guidance

For the practitioner on the mundane path, attention becomes more deliberate. Through mindfulness and Right Effort, coarse chatter weakens, but fabrication remains. It now functions in a skillful rather than a compulsive way.

Directed and sustained thought are still present, but they serve the training. Attention is guided with quiet instructions such as “stay with the breath” or “relax the effort.” Subtle verbal formations appear as monitoring and adjustment. Clinging is reduced but not ended. Attention is skillful, yet it is still doing something and still shaping experience.

The Noble Disciple: Attention as Letting Go

For the Noble Disciple, identity view has been seen through, even though self-making and mine-making may still arise as habits. Because experience is no longer taken as a fixed self, attention no longer organizes experience around a central owner.

When attention moves, it is not immediately taken up as mine. Contact is less likely to lead to a reaction, and proliferation no longer follows automatically. In moments when ignorance is not operating, attention does not function as a conditioning force at all.

As this understanding deepens, the felt need to hold or manage attention drops away. Attention becomes lighter and easier to release. In states of collectedness, directed and sustained attention can cease naturally, not through suppression, but because there is no need to guide experience.

This is expressed in the second jhāna:

With the stilling of directed and sustained attention, he enters and dwells in the second jhāna, which has internal confidence and unification of mind, without directed and sustained attention.

DN2

Here, the subtle activities of aiming and sustaining attention fall silent. Verbal fabrication does not arise because there is no directing or maintaining of an object. Attention is no longer experienced as something being done, and the sense of “I who am attending” fades. Knowing occurs directly, without commentary.

The same principle appears in mindfulness of breathing:

He trains thus: ‘I will calm bodily fabrication.’ He trains thus: ‘I will calm mental fabrication.’

MN118

Calming mental fabrication refers to the stilling of vitakka and vicāra, the subtle activities that organize experience prior to verbalization. When these subside, verbal fabrication does not occur, and what remains is direct knowing.

Seen this way, the training is not about refining control or perfecting attention. It is about seeing the assumptions that give attention its shaping power. As clinging fades, attention naturally loses its compulsive role. What ceases is not awareness, but the tendency of attention to fabricate a world that feels as if it must be managed.

Attention: What One Pays Attention to Grows

One of the core teachings in the discourses is that whatever we place attention on grows. The mind is nourished by what it dwells upon, whether wholesome or unwholesome. If attention is habitually given to greed, aversion, or delusion, these roots deepen. But when attention is turned toward joy, tranquility, and wisdom, these wholesome qualities expand and strengthen.

To purify the mind, we need to use Right Effort to cultivate two key attentional skills:

-

Vitakka, the initial application of attention. It is the turning of the mind away from an unwholesome mind state toward a wholesome one.

-

Vicāra, sustained attention. It maintains attention on the wholesome mind state, investigates it, stays with it, and steadies its presence there.

Just as a skilled bathman mixes bath powder with water into a smooth lather... so too a disciple drenches his body with rapture and pleasure born of seclusion...

AN5.28

In this simile, the Tathāgata shows how vitakka and vicāra function together as the gentle movements of directed and sustained attention. Like the bathman carefully blending powder and water, these two mental activities shape the mind into a unified experience of joy and tranquility born of seclusion.

When we intentionally direct the mind and sustain it upon a particular perception, such as “this is impermanent,” “this is empty of self,” or “this is unsatisfactory,” we are training the mind to return again and again to the liberating characteristics of experience. Over time, this repeated turning and sustaining forms a wholesome habit, inclining the mind naturally toward insight and release.

This is how Right Effort is developed: we deliberately direct attention toward the wholesome and keep it there, nurturing what leads to peace and letting the unwholesome wither through neglect.

Thus, the work is not to purify attention itself but to purify the conditions that give attention its shaping force. As clinging and misperception weaken, the mind-stream becomes clearer and steadier on its own. From that steadiness, collectedness arises naturally, and from collectedness, direct insight unfolds without being driven.

The Energetic Nature of Pāli Terms

Because there is widespread misunderstanding about “thought” and “attention,” it is important to understand that in Pāli the terms vitakka, vicāra, and saṅkhāra are not static nouns. They point to energetic tendencies and causal movements of the mind.

Vitakka refers to the energy of initial placing, the moment attention first lands on or strikes an object.

Vicāra refers to the energy of continued contact, the subtle mental vibration that sustains the object in awareness and keeps attention connected to it.

Vacī-saṅkhāra are the verbal fabrications generated by this contact. They range from proto-thoughts and subtle inner murmuring to fully formed verbal thinking. These fabrications quietly maintain experience as personal, as something known or owned.

When these energies are purified, attention changes in character. What once functioned as an act of possession loses its grip. The sense of “I am attending” gives way to a simpler mode where there is just knowing.

Therefore, directed and sustained attention are not minor technical details of practice. They reveal how experience is fabricated through attention itself. Because of this, the training of attention is central to the path, not as a matter of control, but as a way of understanding and releasing the energetic processes that shape experience.

Attention: Wise Attention

Not understanding what things are fit for attention and what things are unfit for attention, he attends to things unfit for attention and does not attend to things fit for attention.

And what are the things unfit for attention that he attends to?

Whatever things, when attended to, lead to the arising of unarisen sensual desire, or to the increase of arisen sensual desire, to the arising of unarisen desire for existence, or to the increase of arisen desire for existence, to the arising of unarisen ignorance, or to the increase of arisen ignorance: these are the things unfit for attention that he attends to.

And what are the things fit for attention that he does not attend to?

Whatever things, when attended to, do not lead to the arising of unarisen sensual desire, or to the increase of arisen sensual desire, to the arising of unarisen desire for existence, or to the increase of arisen desire for existence, to the arising of unarisen ignorance, or to the increase of arisen ignorance: these are the things fit for attention that he does not attend to.

By attending to things unfit for attention and not attending to things fit for attention, unarisen defilements arise and arisen defilements increase....

He attends wisely to: this is suffering; this is the origin of suffering; this is the cessation of suffering; this is the path leading to the cessation of suffering.

By attending wisely in this way, three fetters are abandoned: identity view, doubt, and attachment to rites and rituals.

MN2

So what is the fire that burns away karmic impurities? It is the fire of insight, and it penetrates most clearly in two modes: seeing and developing.

In MN 2, the Tathāgata describes seven methods for abandoning the taints: seeing, restraining, using, enduring, avoiding, removing, and developing, but only two lead directly to liberation, to the supra-mundane path:

-

Abandoning by seeing: Always, Right Mindfulness comes first. Clear knowing is the doorway, and often, simply seeing a hindrance, without judgment, without clinging, is enough to loosen its grip. Through Right View, we see, “This is not-self. This is impermanent. This is unsatisfactory.” And seeing this way, wrong views begin to dissolve, we stop wrestling with shadows, we see things as they are, and the mind begins to let go.

-

Abandoning by developing: This is the active process. Here, we cultivate the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, and we nourish the wholesome. Each factor—mindfulness, investigation, energy, joy, tranquility, concentration, and equanimity—becomes medicine for the mind. Through their development, the hindrances are not just suppressed; they are uprooted.

The other five methods—restraining, using, enduring, avoiding, and removing—serve as temporary measures, skillful in moments, but not sufficient for liberation. They calm the waters, but they don’t remove the source of turbulence.

So at this point in the Gradual Training, we shift toward creating the causes and conditions for true liberation. We abide in the Four Dwellings of Mindfulness, and from there, generate the wholesome through the Seven Factors of Enlightenment.

As every individual is different, one will need to identify which hindrances affect them the most, understand how and when they arise, recognize their inner strengths to counter each hindrance, and actively cultivate relevant practices to overcome them.

Disciples, considering the internal factor, I do not see any other single factor that is so conducive to the arising of the seven factors of enlightenment as wise attention. For a disciple who is endowed with wise attention, it is to be expected that he will develop and cultivate the seven factors of enlightenment.

And how does a disciple who is endowed with wise attention develop and cultivate the seven factors of enlightenment? Here a disciple develops the enlightenment factor of mindfulness, which is based on seclusion, dispassion, and cessation, and matures in relinquishment.

He develops the enlightenment factor of investigation, energy, joy, tranquility and concentration.

He develops the enlightenment factor of equanimity, which is based on seclusion, dispassion, and cessation, and matures in relinquishment.

In this way a disciple who is endowed with wise attention develops and cultivates the seven factors of enlightenment.

SN46.49

Wise Attention: Yoniso Manasikara

In the teachings, attention is not just a cognitive act but the turning and directing of the mind toward experience. It determines how consciousness meets the world. The discourses describe Wise Attention (yoniso manasikāra) as the root of all wholesome qualities and unwise attention as the root of all defilements.

Attention is one of the components of name in the name-and-form link of dependent arising, which includes feeling, perception, intention, contact, and attention.

At this early point in the chain, these five functions do not yet carry the specific content of individual experiences; they are potential capacities, the interfaces or “mental equipment” that allow for the ability to feel, to recognize, to intend, to make contact, and to attend.

Later in the chain, feeling, craving, clinging, and other processes appear again, but now they function as conditioned events, arising once the mind engages with a specific contact and begins reacting to it.

In other words, before contact, attention acts like a reaching or orienting movement, the mind’s readiness for contact. It is not yet full knowing, but the preparatory turning toward knowing.

Before attention moves, there is intention. Intention conditions the direction in which attention flows, whether toward greed, aversion, or understanding. For this reason, wise attention is not a special kind of attention added on top, but attention that arises in dependence on Right View and Right Intention.

Developing wise attention does not mean forcing attention onto experience. It means allowing experience to be known in a way that reveals its arising and fading, so causes, conditions, and their results become evident on their own. As this understanding deepens, the mind no longer needs to steer attention deliberately.

With practice, attention loses its compulsive, appropriating quality. It becomes steady without effort, like light that illuminates without grasping. From this steadiness, insight matures naturally, leading to dispassion and release.

There are, disciples, things that are the basis for the arising of the seven factors of enlightenment. When one gives wise attention to them, the seven factors of enlightenment arise and come to fulfillment.

SN 46.2

Wise Attention: The Four Noble Truths

To practice Wise Attention, we must use the Four Noble Truths to guide our practice.

The Four Noble Truths are often presented as four separate teachings: suffering, its origin, its cessation, and the path. While this is useful for learning and reflection, it is not how the training actually functions in lived practice. When the mind is being trained to abandon the taints, the four truths do not operate as separate steps or reflections. They function as a single, unified process.

In direct experience, suffering, craving, release, and the path are known together. Stress is felt, the movement of craving that sustains it is recognized, the easing that comes from not feeding that movement is immediately available, and the way forward is already present. The truths are not applied one after another; they operate as one mode of seeing and responding.

This shift is essential for understanding how the hindrances are addressed and how the awakening factors are developed without having to analyze them individually. The hindrances do not arise in isolation; they arise when craving is active and unexamined. When craving is seen clearly and not continued, the hindrances fail to take hold. Likewise, the seven factors are not constructed piece by piece; they emerge naturally as the mind repeatedly inclines toward release.

Seeing the Four Noble Truths as one energy means that the mind stops treating them as concepts to be recalled and starts using them as a living orientation. Stress is immediately recognized as conditioned; the pull toward clinging is felt as unnecessary; the relief that comes from not feeding that pull is directly known; the path, at that point, is simply the mind leaning toward what eases suffering.

Right effort is used directly in this unified functioning. It is not striving or control, but an inclination. The mind naturally turns away from what tightens and inclines toward what releases. Unwholesome states lose momentum because they are not pursued. Wholesome qualities gain strength because the mind repeatedly recognizes their value. In this way, preventing, abandoning, developing, and sustaining occur together as a single directed energy rather than as separate techniques.

Practicing like this, the training accelerates because the mind receives immediate feedback. Clinging is felt as constriction. Non-clinging is felt as relief, calm, or quiet joy. By seeing both in the same field of experience, the mind learns quickly which direction leads forward. Right effort becomes self-reinforcing because it is continuously confirmed by experience.

From this perspective, the four noble truths are not something added at the end of practice. They are what the mind finally sees clearly once its habits of clinging have weakened. At that point, they are no longer four teachings. They are one functioning insight, one movement of understanding and inclination, steadily bringing the taints to an end.

Attention: Developing Concentration

Finally, we must keep in mind that the goal of recognizing the “Sign of the Mind”, dwelling Mind in Mind, and abandoning the hindrances through developing the Seven Factors of Enlightenment is to develop Right Concentration.

Right Concentration does not arise from forcing attention into a narrow focus but from letting go of what scatters it. As unskillful tendencies subside, the mind gathers by itself, becoming unified, steady, and clear.